Genesis

William Goldman, Adventures in the Screen Trade, 1983

Can You Elaborate?

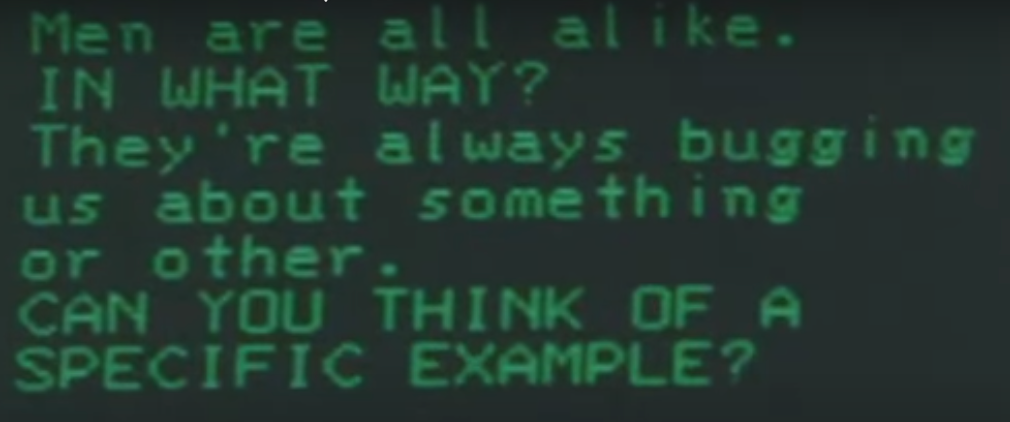

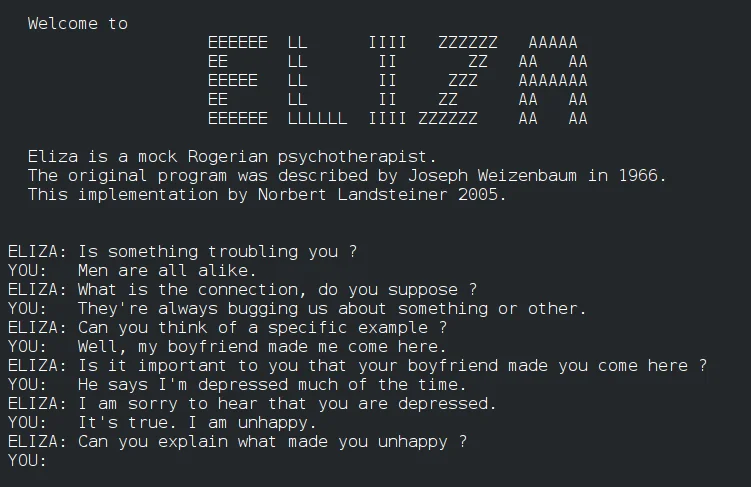

Joseph Weizenbaum hated how his invention, ELIZA (aka DOCTOR), had been cast as an intelligent human therapist.

In his letter to Edward ‘Father of Expert Systems’ Feigenbaum in 1970, Weizenbaum wrote:

The thinking I’ve done so far tells me that the earlier ELIZA system (while canned in some respects) is grossly inefficient in many others.

Its total ignorance of grammar, for example, cannot be underestimated. Also, the structure of ELIZA scripts (e.g., absence of threads) argues from an entirely new perspective, i.e., from that of belief structures.

That did not stop the media from dramatizing the public reaction.

Seven years later, in Computer Power and Human Reason, Weizenbaum pleaded:

The shocks I experienced as DOCTOR became widely known and “played” were due principally to three distinct events.

- A number of practicing psychiatrists seriously believed the DOCTOR computer program could grow into a nearly completely automatic form of psychotherapy. […]

- I was startled to see how quickly and how very deeply people conversing with DOCTOR became emotionally involved with the computer and how unequivocally they anthropomorphized it. […]

- Another widespread, and to me surprising, reaction to the ELIZA program was the spread of a belief that it demonstrated a general solution to the problem of computer understanding of natural language. In my paper, I had tried to say that no general solution to that problem was possible, i.e., that language is understood only in contextual frameworks, that even these can be shared by people to only a limited extent, and that consequently even people are not embodiments of any such general solution. But these conclusions were often ignored.

The reality was much more prosaic.

Eliza used a basic pattern-matching system to extract the user’s intent and repeat back a variation of the question they asked. Its talent was reframing what you posed as a question as if the answer was at the tip of its tongue – if you could just divulge a little more…

Despite not knowing grammar rules, it correctly adjusted the tense and subject of a response to give its discourse the aura of an educated conversationalist.

What made it different was that it could pick out core nuggets of what you had entered, remember them, and regurgitate them later in the conversation. What in today’s parlance may be called

If you asked Eliza a complex question, tried to challenge it, or reached a conversational dead-end, it simply ignored what you were saying and flipped back to a previous point as if recalling a memory. It was a neat parlor trick as if it was paying attention and remembering what you had told it, like a Good Listener.

# Is something troubling you?

ELIZA was an attempt at codifying the famous Turing Test (aka Imitation Game) to see if a computer could fool a human. However, anyone spending more than a few minutes with ELIZA could see the repeating patterns and its failure to provide meaningful answers to questions.

Weizenbaum famously decried how this could be conflated with true intelligence:

[O]nce a particular program is unmasked, once its inner workings are explained in language sufficiently plain to induce understanding, its magic crumbles away; it stands revealed as a mere collection of procedures, each quite comprehensible.

His warnings were prescient:

“Don’t use computers to do what people ought not do.”

That caution applies today, just as much as it did back then.

# Side Note

You’re Probably Wondering How We Ended up Here

I can write a dozen posts on the history of present-day AI, and lots of them have been written.

Instead, for those who like original sources, here’s a reading list of seminal 20th-century Points of Inflection:

| Year | Person(s) | Key Work / Contribution |

|---|---|---|

| 1943 | Warren McCulloch & Walter Pitts | A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity — Foundation of Neural Networks. |

| 1948 | Norbert Wiener | Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine — feedback and control in machines and organisms. |

| 1950 | Alan Turing | Computing Machinery and Intelligence - the Imitation Game. |

| 1956 | Allen Newell, J.C. Shaw, & Herbert Simon | The Logic Theorist — the first running symbolic AI program. |

| 1957 | Noam Chomsky | Syntactic Structures - Introduced generative grammars and the Chomsky Hierarchy. |

| 1958 | Frank Rosenblatt | The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model For Information Storage and Organization In the Brain - showed an algorithm could adapt its parameters based on inputs and improve its performance. |

| 1958 | John McCarthy | Lisp programming language - one of the first AI programming languages featuring symbolic programming. |

| 1965 | Hubert Dreyfus | Alchemy and Artificial Intelligence - predicts failure in AI due to fundamental differences between how human minds and computers operate. |

| 1969 | Marvin Minsky & Seymour Papert | Perceptrons — a critique of neural networks, arguing they had limited capability. |

| 1997 | Hochreiter & Schmidhuber | Long Short-Term Memory - detection of patterns over time and across long sequences. |

| 2014 | Goodfellow et al. | Generative Adversarial Networks - using two networks battling each other, used to generate synthetic images, video, etc. |

| 2017 | Google Research: Vaswani, Shazeer, et al. | Attention is All You Need - use simultaneous attention mechanisms to process sequential data. Kicked off the current GPT craze. |

But let’s not beat around the bush. All this academic talk is for…

The singular event most responsible for sparking the imagination of generations of researchers was a

I’m Sorry, Dave…

The

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

It murdered. It disobeyed orders. And it tried to protect itself at all costs, while singing Daisy, Daisy.

It helped that the science advisor on the film was none other than Marvin Minsky, the eminent co-founder of the CSAIL / MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, giving the whole affair a solid whiff of credibility. The book Hal’s Legacy: 2001’s Computer as Dream and Reality, published in 1997, attempted to explain the film’s legacy.

But let’s be honest. I think it’s pretty obvious.

Many people took it as a cautionary tale. A select few considered it a shining light, guiding the path forward.

A Path Forward

Voice Recognition

For decades, voice recognition had been considered a key component of understanding humans. Let’s take a walk down memory lane.

Audrey (1952)

Audrey used custom voice recognition hardware built by AT&T Bell Labs to recognize the spoken digits ‘0’ to ‘9’. It had to be trained on a specific person’s voice, but amazingly,

IBM Shoebox (1962)

Shown at the IBM Pavilion at the Seattle World Fair. The device could recognize 16 words, including numbers. Laugh all you want, but that was a remarkable feat, given the state of the technology.

PARRY (1972)

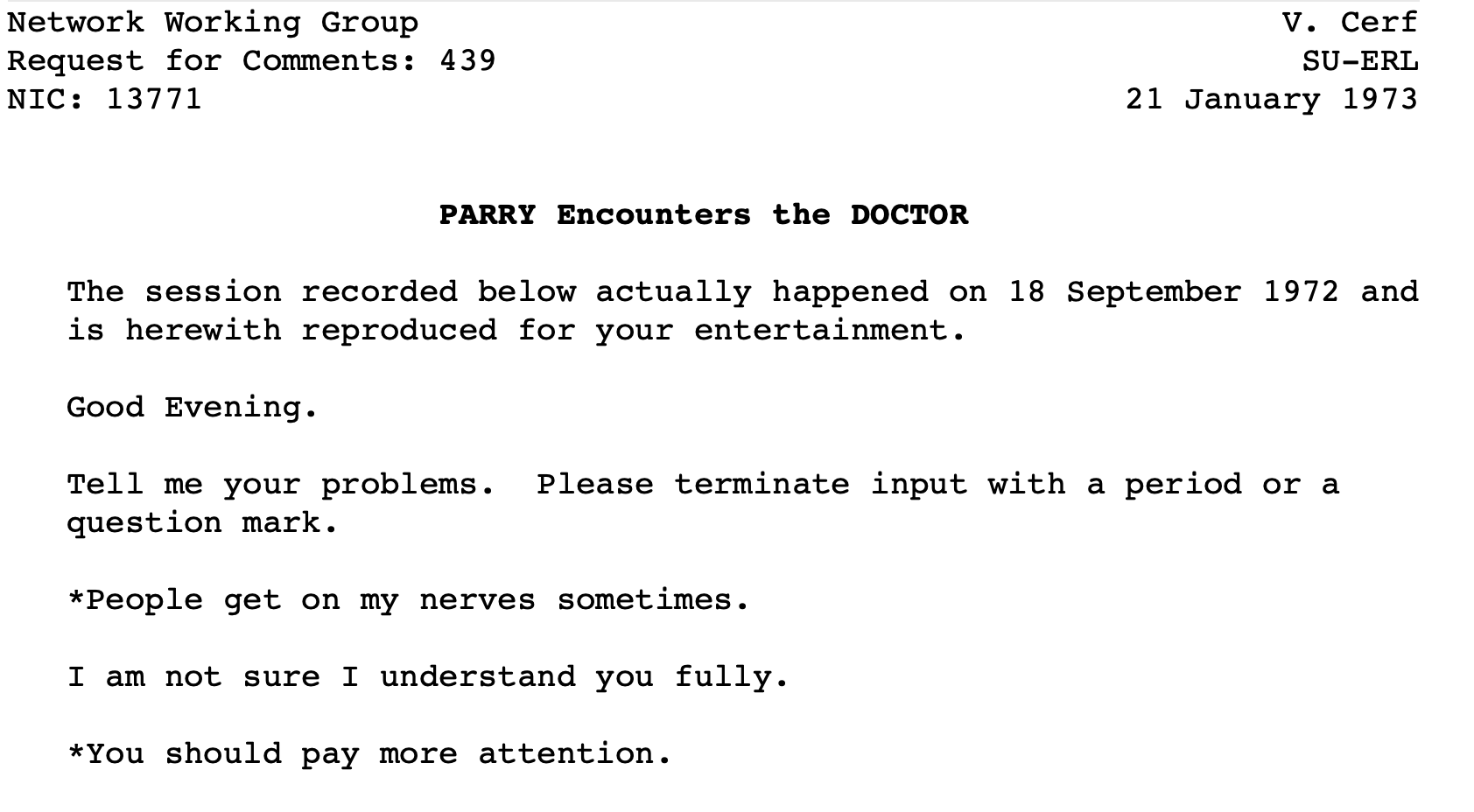

It was based on the same core technology as ELIZA, but it headed into darker terrain, given that the name stood for Paranoia. It simulated a Paranoid Schizophrenic patient.

At one point, PARRY had a head-to-head conversation with DOCTOR that might seem familiar to today’s observers of online discussion groups:

[PARRY] I used to go to the track every week.

[ELIZA] What does that suggest to you?

[PARRY] I avoid racetracks now because the races are fixed.

[ELIZA] Is that the real reason?

[PARRY] I’d rather not discuss it.

[ELIZA] What else would you like to discuss?

[PARRY] That’s something I don’t want to go into.

[ELIZA] Does that trouble you?

…

Six years later, the same attribute would be used to good effect in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

“You think you’ve got problems? What are you supposed to do if you are a manically depressed robot? No, don’t try to answer that. I’m fifty thousand times more intelligent than you and even I don’t know the answer. It gives me a headache just trying to think down to your level.”

- Marvin the Robot

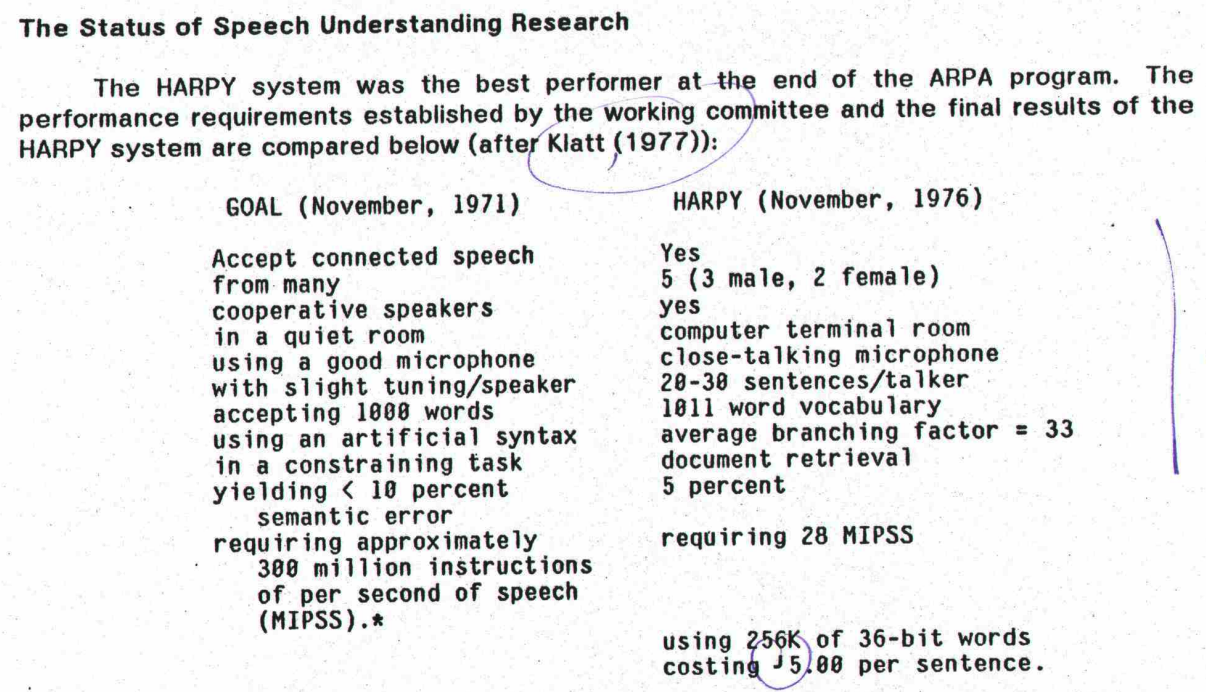

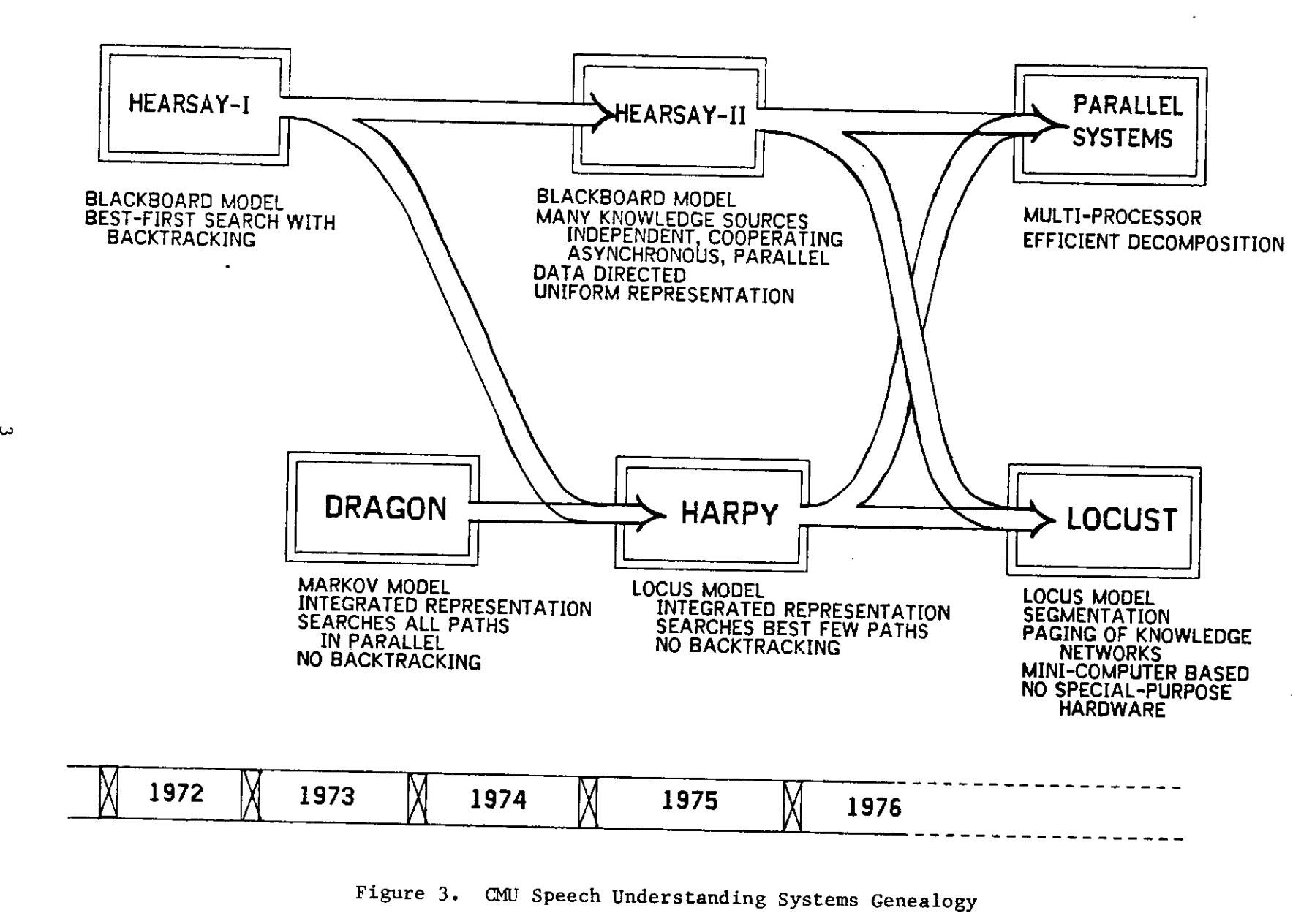

HARPY (1972)

Harpy’s test results were impressive:

An even deeper dive that includes several other contemporary systems showed Harpy to be a formidable bit of tech:

Dragon NaturallySpeaking (1975)

This was one of the first commercial

As it happened, James K. Baker, a rising force in the world of speech recognition technology, was finishing his PhD thesis at Carnegie Mellon during the DARPA-funded research boom. In his landmark 1975 dissertation, “Stochastic Modeling as a Means of Automatic Speech Recognition,” Baker explored the uses of Hidden Markov models to recognize words from unrecognized sounds. This foundational research led to the first commercially viable speech recognition software.

In 1982, Baker and his wife, Janet MacIver Baker, formed Dragon Systems Inc. In 1997, Dragon released the first consumer-grade commercial voice recognition product, Dragon NaturallySpeaking. This software’s selling point was that

for the first time in decades of speech recognition research and development, the user did not need to speak haltingly with unnatural pauses for the benefit of the machine . Dragon’s software was the first to process continuous natural speech and remains in use today.

The company had to go through a series of acquisitions and mergers, starting with Lernout & Hauspie, then ScanSoft and Nuance, before finally landing at Microsoft.

# Side Note

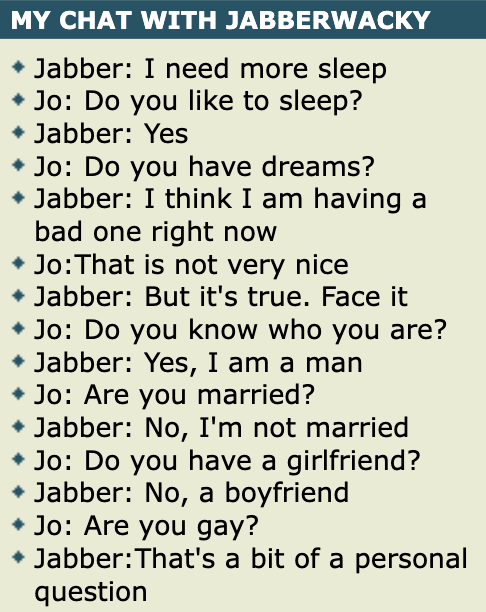

Jabberwacky (1982)

Jabberwacky (a variation on the Lewis Carroll poem) began as a conversational program on a Sinclair ZX81, but it evolved over time to learn from human conversation.

Rollo Carpenter, creator of Jabberwocky, predicting a chattering bot:

“It will then start to have a home in physical objects, little robots that are a talking pet.”

…

If I have my way, people will be walking around, sitting, cooking and more with one on their shoulder, talking in their ear.”

You can try a modern version for yourself.

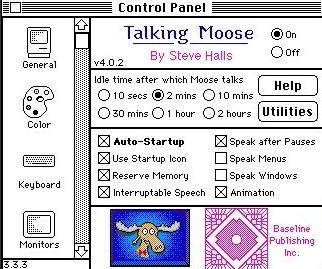

Talking Moose (1986)

Talking Moose was an early Mac companion that popped onto the screen, narrating what was happening on the system with humorous quips. It used MacinTalk text-to-speech technology and made a good novelty demo to show friends (and their 6-year-old kids who found it hilarious).

What made it especially unique was that

This is where an assistant encroaches into the enclosing operating system, a feature Apple later added to Siri and incorporated into iOS and MacOS.

Dr. Sbaitso (1992)

Developed by Creative Labs (of Sound Blaster fame) to show off the capabilities of their PC Sound Cards, it was one of the first chatbots to marry ELIZA-style interactions with text-to-voice output.

Dr. Sbaitso was later turned into a game. There is an emulated version you can try.

ALICE (Artificial Linguistic Internet Computer Entity) aka Alicebot (1995)

ALICE was a rule-based chatbot, famously inspiring the 2013 Oscar-nominated Spike Jonze movie Her. The movie featured Scarlett Johansson as the AI Chatbot Samantha.

A decade later, emulating her voice would cause a legal dust-up between Johansson and OpenAI.

Microsoft Bob (1995)

Microsoft was looking to simplify the PC’s user experience and make it more user-friendly. Bob was a re-imagining of the operating system interface. It featured several animated assistant characters, including a dog called Rover.

BOB was based on Microsoft Agent technology, which incorporated speech recognition, text-to-speech, and access to Office and Windows environments.

# NASA Digital Library

Clippy (1997)

Clippy was Microsoft’s attempt to integrate an embedded assistant that would help new users unfamiliar with Microsoft Office. Clippy used the same Microsoft Agent technology as Bob and, unfortunately, faced similar criticisms.

Clippy, however, was foisted onto millions of standard Windows computers running Office 97, much like U2’s Songs of Innocence was crammed onto iTunes without users asking for it.

# Connect the Dots

Prody Parrot (1999)

This was a Windows assistant that flew around the screen, squawking as it read aloud messages and offered to help with desktop tasks. Yes, it was as annoying as it sounds.

# Side Note

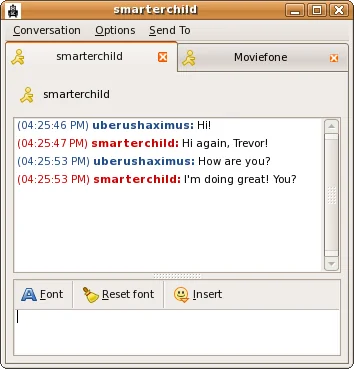

SmarterChild (2001)

This was an add-on Instant Messenger bot for AIM and MSN. It used conversational AI alongside real-time data like stocks and weather.

# External Services

AI Winter, Part Deux

It was around 2001 that AI Assistant technology took a nearly decade-long break. The Internet started taking off, and as we all know, the iPhone appeared.

It shook up the tech world.

# iPhone Announcement

Meanwhile…

Text-to-voice and voice-to-text technology in the 1980s needed to get much, much better.

And it did.

Enter DECTalk, a standalone hardware device that allows you to send a string of text (with embedded ‘escape’ characters) via serial port commands. This could change voices, intonation, timing, pauses, and other variables. The technology behind it was hardcore fascinating.

DECTalk was useful to the burgeoning Interactive Voice Response (IVR) market. Enterprises were looking to save call center costs and allow customers to use their touch-tone phones to navigate phone menus on their own. IVR applications would accept user input (in the form of digits 0-9, *, and #), look up information from a database, fill in a template, and have DECTalk speak it back in a human-sounding voice.

It was also used by the National Weather Service and, famously, Stephen Hawking.

# Personal Anecdote

The Next Leap Forward

Further Reading

- Speech Recognition Through the Decades: How We Ended Up With Siri, PCWorld, 2011.

- The machines that learned to listen (BBC, 2017).

- A Brief History of ASR: Automatic Speech Recognition.

- Voice Search and Google: The Past, Present, and Future. Synup, 2019.

- Speech Recognition from Audrey to Alexa – A Brief History, DictateIT, 2021.

- AUDREY, ALEXA, HAL, AND MORE, by Dag Spicer in the Computer History Museum blog (2021).

- Timeline of speech and voice recognition, Wikipedia.

In this section, we covered the fundamental technological that were needed to be able to start thinking about AI Companions.

Next, we’ll stay in historical mode, by looking into how these were put together in software and hardware products. There were a lot of misses, but also a few familiar hits.

Stay tuned.

Title Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash