True Majesty Still Awaits

In 1970, the Director of MIT’s AI Lab made a prediction in Life Magazine

Marvin Minsky of MIT’s Project Mac, a 42-year-old polymath who has made major contributions to Artificial Intelligence, recently told me with quiet certitude:

‘In from three to eight years we will have a machine with the general intelligence of an average human being. I mean a machine that will be able to read Shakespeare, grease a car, play office politics, tell a joke, have a fight. At that point the machine will begin to educate itself with fantastic speed. In a few months it will be at genius level and a few months after that its powers will be incalculable.’’

In 1998, he backtracked on that claim:

Oh, that Life quote was made up. You can tell it's a joke.

He went on to hedge:

Herbert Simon said in 1958 that a program would be chess champion in ten years, and, as we know, the IBM group has done extremely well, but even now [Deep Blue] is not the undisputed champion. As for optimism, it depends on what you mean. I believed in realism, as summarized by John McCarthy’s comment to the effect that

if we worked really hard, we'd have an intelligent system in from four to four hundred vears .

His main complaint was that the goals weren’t pitched high enough:

Only a small community has concentrated on general intelligence. No one has tried to make a thinking machine and then teach it chess—or the very sophisticated oriental board game Go. So Clarke made the same mistake that Herbert Simon made in the sixties, that AI was progressing so well and would continue to progress that we should start by concentrating on particular problems, such as Go or chess. But that’s the wrong idea. I’he bottom line is that we really haven’t progressed too far toward a truly intelligent machine.

We have collections of dumb specialists in small domains; the true majesty of general intelligence still awaits our attack. – Marvin Minsky - Hal’s Legacy

Famed Designer Don Norman, looking back at 2001: A Space Odyssey said:

Human intelligence means more than intellectual brilliance: it means true depth of understanding, including shared cultural background and knowledge —- the sort of background that takes decades to acquire. It also means what Daniel Goleman refers to as emotional intelligence: the knowledge and skills of social interaction, including the ability to cooperate and compete successfully with colleagues, friends, and rivals. In the 1960s, workers in the related fields of cognitive psychology and artificial intelligence ignored emotions and social interaction and focused exclusively on sheer intellect: reasoning, remembering, problem solving, decision making, and thought. At the time, the field appeared to be making rapid progress.

We now know that progress was so rapid because we were solving the easy problems first ; but in the heady optimism of the day, many assumed that the early successes signaled an early victory.Today, we are far less cocky.

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) means many different things to different people, but

the most important parts of it have already been achieved by the current generation of advanced AI large language models such as ChatGPT, Bard, LLaMA and Claude. These “frontier models” have many flaws: They hallucinate scholarly citations and court cases, perpetuate biases from their training data and make simple arithmetic mistakes.Fixing every flaw (including those often exhibited by humans) would involve building an artificial superintelligence, which is a whole other project.

That is one of the finest examples of:

However, they should be commended for not mincing words:

But the key property of generality?

It has already been achieved.

Yoshua Bengio, et al in May 2024:

We don’t know for certain how the future of AI will unfold. However, we must take seriously the possibility that highly powerful generalist AI systems—outperforming human abilities across many critical domains—will be developed

within the current decade or the next.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI in January 2025:

We are now confident we know how to build AGI as we have traditionally understood it.

We believe that, in 2025, we may see the first AI agents “join the workforce” and materially change the output of companies . We continue to believe that iteratively putting great tools in the hands of people leads to great, broadly-distributed outcomes.

Google DeepMind CEO Demis Hassabis - January 2025:

Well look, I mean, of course the last few years have been incredible amount of progress, maybe over the last decade plus, this is what’s on everyone’s lips right now, and the debate is how close are we to AGI, what’s the correct definition of AGI, we’ve been working on this for more than twenty-plus years, we’ve sort of had a consistent view of AGI being a system that’s capable of exhibiting all the cognitive capabilities humans can. I think we’re getting closer and closer, but I think we’re still probably a handful of years away.

…

I think, you know, I would say probably,

three to five years away. …

I think so. There’s a lot of hype in the area, of course. I mean some of it is very justified. I would say that AI research today is over-estimated in the short-term, I think probably over-hyped, at this point, but still under-appreciated and very under-rated about what it’s going to do in the medium to long-term. So we’re still in that kind of weird kind of space. And

I think part of that is there's a lot of people that need to do a lot of fund-raising, a lot of startups and other things, and so I think we're going to have quite a few outlandish and slightly exaggerated claims, and I think that's a bit of a shame, actually .

Dario Amadei, CEO of Anthropic, in October 2024:

What powerful AI (I dislike the term AGI) will look like, and when (or if) it will arrive, is a huge topic in itself. It’s one I’ve discussed publicly and could write a completely separate essay on (I probably will at some point). Obviously, many people are skeptical that powerful AI will be built soon and some are skeptical that it will ever be built at all.

I think it could come as early as 2026, though there are also ways it could take much longer .

Yann LeCun, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist, in May 2025, doing a reality check:

We are not going to get to human level AI by just scaling up LLMs. This is just not going to happen okay... There's no way okay. Whatever you can hear from some of my more adventurous colleagues, it's not going to happen within the next two years. There’s absolutely no way in hell, to you know, pardon my French, the you know the idea that we’re we’re going to have you know a country of genius in a data center is absolutely BS. There’s absolutely no way. What we may have, maybe, is systems that are trained on sufficiently large amounts of data, that any question that any reasonable person may ask, will find an answer through the systems. And you will feel like you have a PhD sitting next to you, but it’s not a PhD you have sitting next to you, it’s a system with a gigantic memory and retrieval ability. Not a system that can invent solutions to new problems, which is really what a PhD is.

Google DeepMind researchers, in July 2024, also take a far more cautious approach:

In this position paper, we argue that

it is critical for the AI research community to explicitly reflect on what we mean by “AGI,” and aspire to quantify attributes like the performance, generality, and autonomy of AI systems. Shared operationalizable definitions for these concepts will support: comparisons between models; risk assessments and mitigation strategies; clear criteria from policymakers and regulators; identifying goals, predictions, and risks for research and development; and the ability to understand and communicate where we are along the path to AGI.

They go on to define multiple Principles and Levels of AGI, placing many in the

The main question that is yet to be addressed is

One thing writing this essay has made me realize is that

it would be valuable to bring together a group of domain experts (in biology, economics, international relations, and other areas) to write a much better and more informed version of what I’ve produced here. It’s probably best to view my efforts here as a starting prompt for that group.

The broader question is should expertise in, say, sports or politics, be assessed the same way as expertise in astrophysics or medicine? If we hold them all to the same singular General criteria, then we end up with the sort of moving goalposts that leads to the Blind men and Elephant parable.

Agüera y Arcas and Norvig are ready to declare domain-specific intelligence as trivial:

“General intelligence” must be thought of in terms of a multidimensional scorecard, not a single yes/no proposition. Nonetheless,

there is a meaningful discontinuity between narrow and general intelligence : Narrowly intelligent systems typically perform a single or predetermined set of tasks, for which they are explicitly trained. Even multitask learning yields only narrow intelligence because the models still operate within the confines of tasks envisioned by the engineers. Indeed, much of the hard engineering work involved in developing narrow AIamounts to curating and labeling task-specific datasets .

Google DeepMind researchers are a bit more circumspect in their assessment:

However, if you were to ask 100 AI experts to define what they mean by “AGI,”

you would likely get 100 related but different definitions.

The One Less Traveled By

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth;

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same,

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back.

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

The Road Not Taken, by Robert Frost

We can break the AGI question into three parts:

- Is ‘AGI’ a single thing or a combination of things?

- Can you achieve ‘AGI’ through the statistical/generative approach or do you need to model other human concepts, like metaphor or emotion?

- Why do we even care about ‘AGI?’

The last one is easy.

General Intelligence has been the goal of all this work since the early 20th Century. Humans are tool-builders, and having a tool that can improve one’s ability has been a constant in human evolution. Whether this is valid is a whole other question. But let’s stipulate that we care about AGI.

Question 1 is where many researchers diverge.

The LLMs are already there gang are left with having to address the fallibility and failings of the current approach. There’s the inevitable problem of Hallucination but also that of Doom Loops in multi-step (aka agentic) operations, and significant security problems with prompt injection:

A single silver bullet defense is not expected to solve this problem entirely. We believe the most promising path to defend against these attacks involves a combination of robust evaluation frameworks leveraging automated red-teaming methods, alongside monitoring, heuristic defenses, and standard security engineering solutions.

There’s also the lethal trifecta problem:

We have seen this pattern so many times now: if your LLM system combines access to private data, exposure to malicious instructions and the ability to exfiltrate information (through tool use or through rendering links and images) you have a nasty security hole.

Google offers a clear path to creating doamin-specific LLMS:

The world of AI has undergone a transformation with the rise of large language models (LLMs). These advanced models, often regarded as the zenith of current natural language processing (NLP) innovations, excel at crafting human-like text for a wide array of domains. A trend gaining traction is the tailoring of LLMs for specific fields — imagine chatbots exclusively for lawyers, for instance, or solely for medical experts.

However, this type of customization is more of a pragmatic approach. We’ll come back to that later.

Let’s tackle Question 2: is the current LLM/Generative Model sufficient to reach ‘human-like’ machine intelligence or do you need to dive deeper into really understanding human cognition.

# Full DisclosureI’m firmly in the camp of the latter, believing that you will never reach true machine intelligence without a deep understanding of human intelligence.

If you disagree, you won’t like what comes next. Feel free to jump ahead or bail out. Thanks for hanging in this far.

Semantics

One of the attempts at extending an LLM to handle external data was through Retrieval Augmented Generation:

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) is the process of optimizing the output of a large language model, so it references an authoritative knowledge base outside of its training data sources before generating a response. Large Language Models (LLMs) are trained on vast volumes of data and use billions of parameters to generate original output for tasks like answering questions, translating languages, and completing sentences. RAG extends the already powerful capabilities of LLMs to specific domains or an organization’s internal knowledge base, all without the need to retrain the model. It is a cost-effective approach to improving LLM output so it remains relevant, accurate, and useful in various contexts.

Most RAG integration attempts tied an LLM to a SQL-type database, like pgDash offering access to Postgres databases or MongoDB, Oracle, DataBricks, or Pinecone.

OpenAI captured it succinctly:

RAG is especially helpful when your GPT needs to answer questions about content that isn’t part of its training data — such as company-specific documentation, internal processes, or recent events.

The problem is this access to external data does not suddenly imbue an LLM with deeper knowledge. There is no deeper semantic knowledge gained from the underlying data. In the data management world, this semantic connectivity is often modeled as a Graph Database:

A Neo4j graph database stores data as nodes, relationships, and properties instead of in tables or documents. This means you can organize your data in a similar way as when sketching ideas on a whiteboard.

And since graph databases are not restricted to a pre-defined model, you can take more flexible approaches and strategies when working with them.

There are a large number of Graph Database vendors out there and its commercial value was recognized early by none other than Facebook’s Graph API. What was needed was Semantic Search:

Semantic search is a data searching technique that focuses on understanding the contextual meaning and intent behind a user’s search query, rather than only matching keywords. Instead of merely looking for literal matches between search queries and indexed content, it aims to deliver more relevant search results by considering various factors, including the relationships between words, the searcher’s location, any previous searches, and the context of the search.

But regular Semantic Search had its limitation. Combinging search with graphs could open much larger vistas. This means that data Nodes can be loosely associated with each other. Adding Graph data to RAG, we end up with GraphRAG:

GraphRAG is a structured, hierarchical approach to Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG), as opposed to naive semantic-search approaches using plain text snippets. The GraphRAG process involves extracting a knowledge graph out of raw text, building a community hierarchy, generating summaries for these communities, and then leveraging these structures when perform RAG-based tasks.

Progress on GraphRAG seems to have slowed down. With the advent of MCP (covered elsewhere), access to external data has moved on to a different technique. Access to a broad range of information (going wide) is now seen as more important than semantic analysis (going deep).

Just an Engineering Problem

Not a single one of the AGI papers, posts, and essays reference the term

In Artificial General Intelligence, published in 2007, Goertzel and Pennachin wrote:

One almost sure way to create artificial general intelligence would be to exactly copy the human brain, down to the atomic level, in a digital simulation. Admittedly, this would require brain scanners and computer hardware far exceeding what is currently available. But if one charts the improvement curves of brain scanners and computer hardware, one finds that it may well be

plausible to take this approach sometime around 2030-2050. This argument has been made in rich detail by Ray Kurzweil in [34, 35]; and we find it a reasonably convincing one. Of course, projecting the future growth curves of technologies is a very risky business. Butthere’s very little doubt that creating AGI in this way is physically possible.

We’re coming up on the 2030 prediction. Luckily, they left a 20-year range in there to cover unforeseen issue. They continue:

In this sense,

creating AGI is “just an engineering problem.” We know that general intelligence is possible, in the sense that humans – particular configurations of atoms – display it. We just need to analyze these atom configurations in detail and replicate them in the computer. AGI emerges as a special case of nanotechnology and in silico physics.

Perhaps a book on the same topic as this one,

written in 2025 or so , will contain detailed scientific papers pursuing the detailed-brain-simulation approach to AGI. At present, however, it is not much more than a futuristic speculation. We don’t understand enough about the brain to make detailed simulations of brain function. Our brain scanning methods are improving rapidly but at present they don’t provide the combination of temporal and spatial acuity required to really map thoughts, concepts, percepts and actions as they occur in human brains/minds.

It’s still possible, however, to use what we know about the human brain to structure AGI designs. This can be done in many different ways.

Most simply, one can take a neural net based approach, trying to model the behavior of nerve cells in the brain and the emergence of intelligence therefrom .

If you recall, simulating at the atomic level was what R.U.R. was all about (and where it went wrong).

Fortunately, we haven’t yet gone that way, but most of the recent advances have come at the level of emulating Neural Networks, but even that may not be enough:

IBM Fellow Francesca Rossi, past president of the Association of the Advancement for Artificial Intelligence, which published the survey, is among the experts who question whether bigger models will ever be enough. “We’ve made huge advances, but AI still struggles with fundamental reasoning tasks,” Rossi tells IBM Think. “To get anywhere near AGI, models need to truly understand, not just predict.”

…

The core problem, Rossi says, is that

while neural networks can recognize statistical patterns, they don’t inherently understand concepts. They can generate responses that sound correct, without truly grasping the meaning behind them. And without an explicit structure for logic and reasoning, AI remains prone to hallucinations, and unreliable decision-making.

Let’s cut Goertzel and Pennachin some slack:

Or one can proceed at a higher level,

looking at the general ways that information processing is carried out in the brain, and seeking to emulate these in software.

Mistakes Have Been Made

In the 2025 SuperBowl, Google ran an ad for a Wisconsin dairy farmer using Google’s Gemini AI to create an ad for Wisconsin Smoked Gouda. According to the Verge:

Google has edited Gemini’s AI response in a Super Bowl commercial to remove an incorrect statistic about cheese. The ad, which shows a small business owner using Gemini to write a website description about Gouda, no longer says the variety makes up “50 to 60 percent of the world’s cheese consumption.”

…

In the edited YouTube video, Gemini’s response now skips over the specifics and says Gouda is “one of the most popular cheeses in the world.”

These are all errors that could have been avoided, had a human stepped in, verified the work, and passed it down in the workflow. But as more autonomy is ceded to computers, the possibility of a knowledgeable, motivated human to inject themselves into the process is diminished.

The consequences of this real-life problem were small. A failure to properly test the outcomes have potentially more severe consequences:

There’s a saying in the mushroom-picking community that all mushrooms are edible but some mushrooms are only edible once.

That’s why, when news spread on Twitter of an app that used “revolutionary AI” to identify mushrooms with a single picture, mycologists and fungi-foragers were worried. They called it “potentially deadly,” and said that if people used it to try and identify edible mushrooms, they could end up very sick, or even dead.

… The app in question was developed by Silicon Valley designer Nicholas Sheriff, who says it was only ever intended to be used as a rough guide to mushrooms. When The Verge reached out to Sheriff to ask him about the app’s safety and how it works, he said the app wasn’t built for “mushroom hunters, it was for moms in their backyard trying to ID mushrooms.”

Sheriff added that he’s currently pivoting to turn the app into a platform for chefs to buy and sell truffles.

In 2023, The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) was forced to remove its chatbot for offering potentially harmful advice:

“It came to our attention [[Monday]] night that the current version of the Tessa Chatbot, running the Body Positive program, may have given information that was harmful,” NEDA said in an Instagram post. “We are investigating this immediately and have taken down that program until further notice for a complete investigation.”

The statement came less than a week after the organization announced it would be entirely replacing its human staff with AI.

In October, New York City announced a plan to harness the power of artificial intelligence to improve the business of government. The announcement included a surprising centerpiece: an AI-powered chatbot that would provide New Yorkers with information on starting and operating a business in the city.

The problem, however, is that the city’s chatbot is telling businesses to break the law.

Five months after launch, it’s clear that while the bot appears authoritative, the information it provides on housing policy, worker rights, and rules for entrepreneurs is often incomplete and in worst-case scenarios

“dangerously inaccurate,” as one local housing policy expert told The Markup.

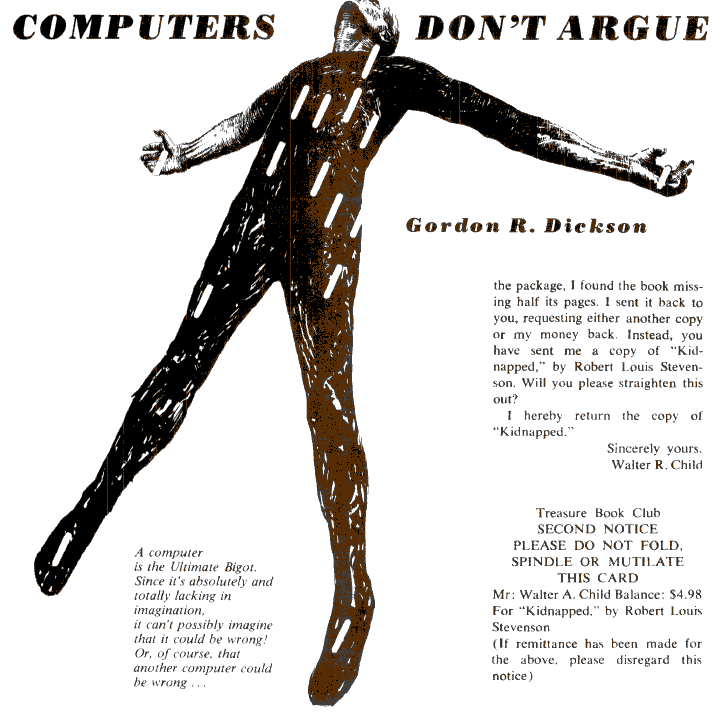

In Computers Don’t Argue, a short-story published in 1965 by Gordon R. Dickson, he lampooned what could happen if humans put all their trust into computerized processes.

In this story, the protagonist Walter A. Child’s starts with a mistaken $4.98 computer-generated bill for his book club membership. It ends [spoiler alert] with a conviction and a death sentence, requiring intervention by the Governor:

FOR THE SOVEREIGN STATE OF ILLINOIS

I, Hubert Daniel Willikens, Governor of the State of Illinois, and invested with the authority and powers appertaining thereto, including the power to pardon those in my judgment wrongfully con- victed or otherwise deserving of executive mercy, do this day of July 1. 1966 do announce and proclaim that Walter A. Child (A. Walter) now in custody as a consequence of erroneous conviction upon a crime of which he is en- tirely innocent, is fully and freely pardoned of said crime. And 1 do direct the necessary authorities having custody of the said Walter A. Child (A. Walter) in whatever place or places he may be held, to immediately free, release, and allow unhindered departure to him…

However, another computerized error prevents the pardon from getting delivered in time:

Interdepartmental Routing Service PLEASE DO NOT FOLD. MUTILATE, OR SPINDLE THIS CARD

Failure to route Document properly. To: Governor Hubert Daniel Willikens Re: Pardon issued to Walter A. Child, July 1, 1966

Dear State Employee:

You have failed to attach your Routing Number. PLEASE: Resubmit document with this card and form 876, ex- plaining your authority for placing a TOP RUSH category on this document…

There are many real-life examples, from so-called

What is the connective tissue of all these cases? A lack of training data? Failure to place HITL (humans in the loop)? A rush to save expenses by laying off expensive human labor?

Or is it something deeper?

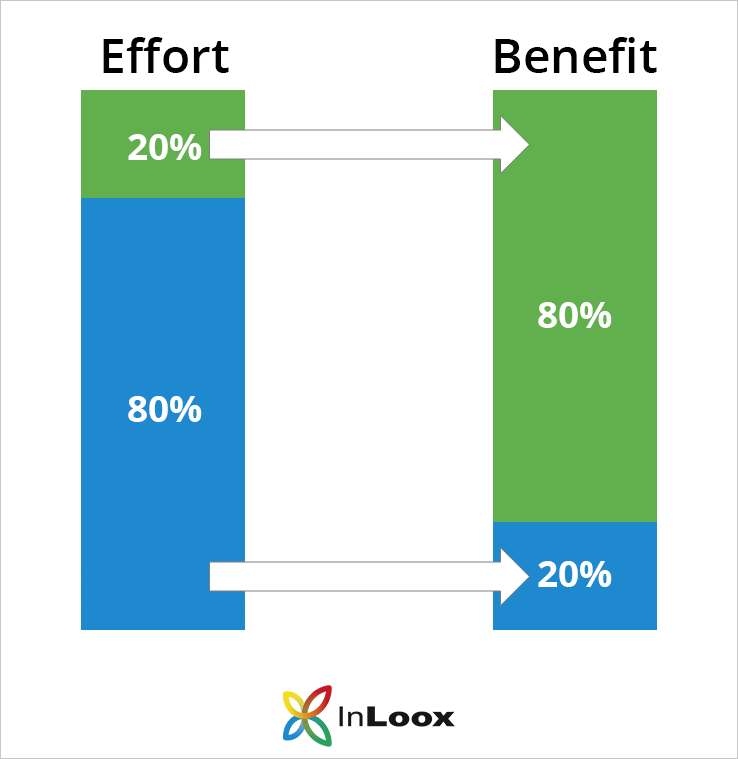

The Pareto Principle

In 1941, management consultant Juan M. Juran coined the term Pareto Principle to indicate that “20% of your actions/activities will account for 80% of your results/outcomes.”

Pareto Principle has evolved as a shorthand that

The actual ratio isn’t sacrosanct. It can be 90/10, or 70/30. It stands for the fact that the proverbial low-hanging fruit should not be mistaken for a solution to the larger problem.

A similar one is Mo’s Law:

You can’t get to the moon by climbing successively taller trees.

Let’s not forget the Dreyfus First Step Fallacy).

Another quote: https://the-decoder.com/the-four-big-misconceptions-of-ai-research/

Need to get access to Dreyfus article and quote.

Going Deep

Hofstadter and Sander in Surfaces and Essences write:

Kicking the Stone

Closing Thoughts

Harvard Data Science Review: Toward a Theory of AI Errors: Making Sense of Hallucinations, Catastrophic Failures, and the Fallacy of Generative AI:

What is becoming clear is that our new technologies are not only astonishing and incredibly powerful, but also

fallible, inaccurate, and at times completely nonsensical . To make sense of this fallacy, the term ‘AI hallucination’ has become widespread in the tech industry, the media, and the public imaginary. Google, Microsoft, and OpenAI all publicly engaged with the problem.

Anthropomorphism in AI: hype and fallacy:

Projecting human capabilities onto artificial systems is a relatively new manifestation of a long-standing and natural phenomenon, but in the realm of AI, this may lead to serious ramifications. The above offers some telling examples of anthropomorphism in AI but does not and indeed cannot provide an exhaustive account of this phenomenon or its connection to hype. Nevertheless, it seems fair to conclude that anthropomorphism is part of the hype surrounding AI systems because of its role in exaggerating and misrepresenting AI capabilities and performance. Furthermore, such over-inflation and misrepresentation is nothing mysterious. It is simply

due to projecting human characteristics onto systems that do not possess them .…

As a kind of fallacy, then, anthropomorphism involves a factually erroneous or unwarranted attribution of human characteristics to non-humans. Given this,

when anthropomorphism becomes part of reasoning it leads to unsupported conclusions .

Title image credit: Flickr