Training

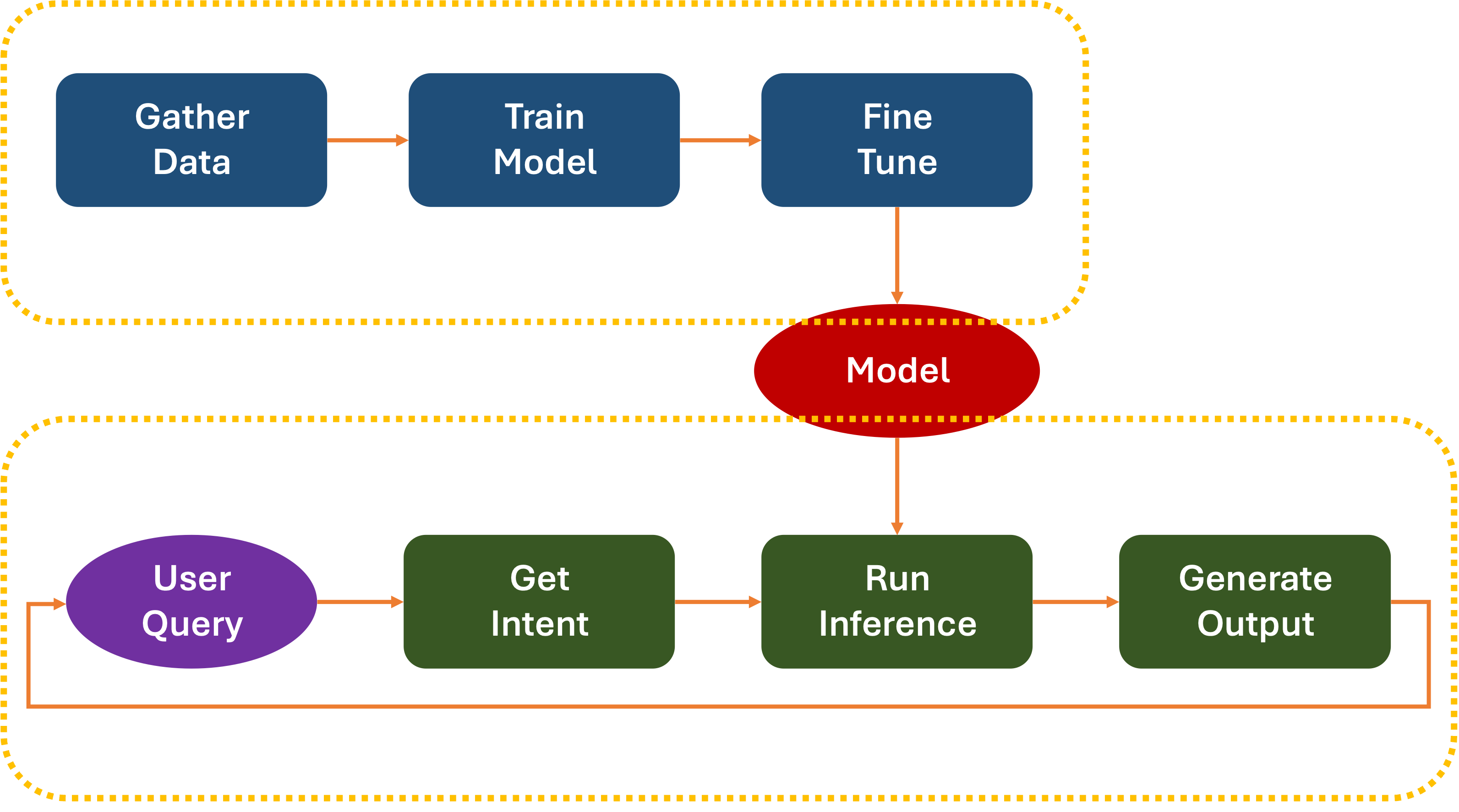

At a high level, AI models have a common workflow:

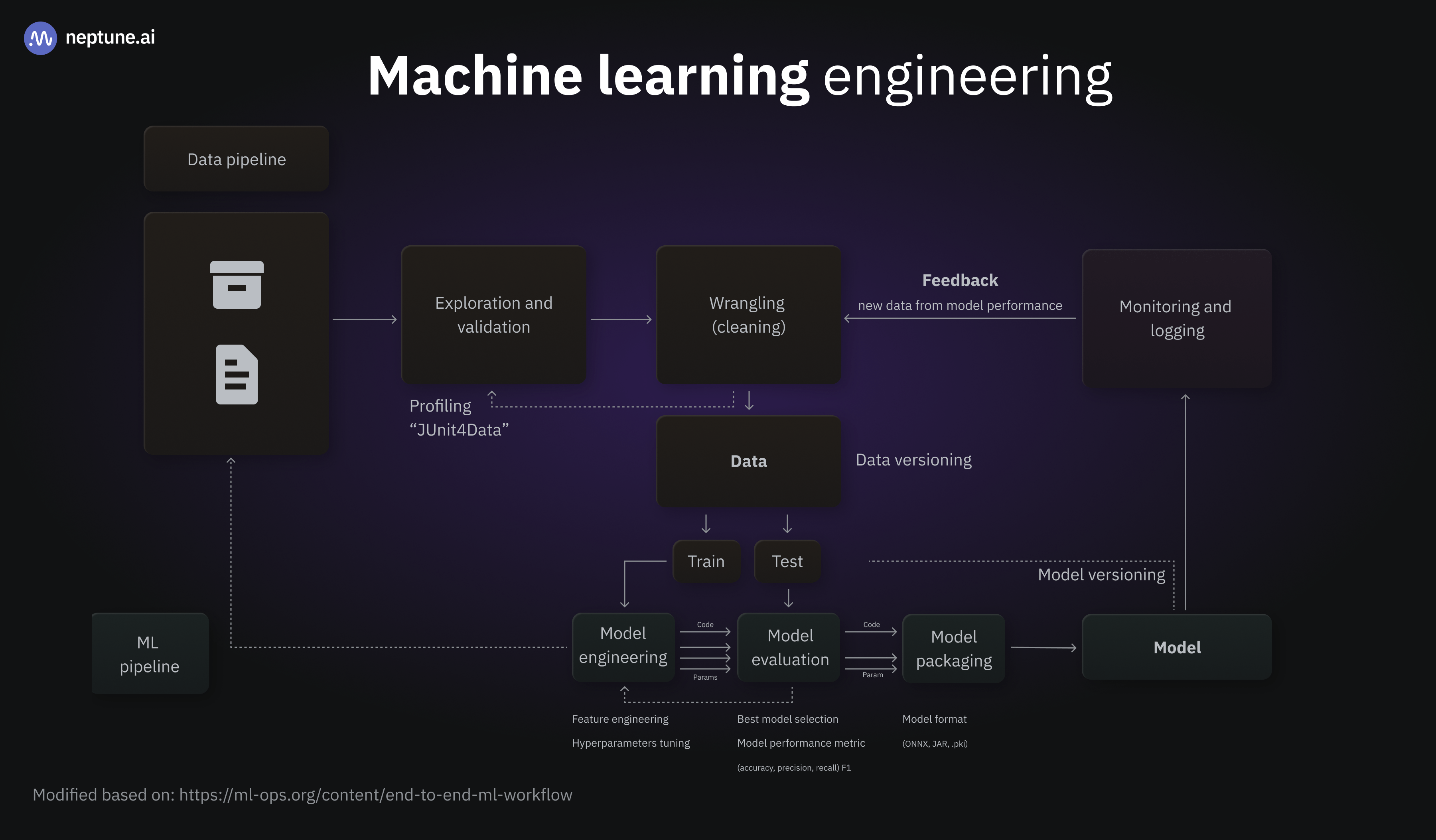

As you might imagine, the actual workflow is a lot more complicated:

In production, the model is continually updated and refreshed. Google recommends daily updates:

Almost all models go stale. Some models become outdated more quickly than others. For example, models that recommend clothes typically go stale quickly because consumer preferences are notorious for changing frequently. On the other hand, models that identify flowers might never go stale. A flower’s identifying characteristics remain stable.

Most models begin to go stale immediately after they’re put into production. You’ll want to establish a training frequency that reflects the nature of your data. If the data is dynamic, train often. If it’s less dynamic, you might not need to train that often.

Train models before they go stale. Early training provides a buffer to resolve potential issues, for example, if the data or training pipeline fails, or the model quality is poor.

A recommended best practice is to train and deploy new models on a daily basis. Just like regular software projects that have a daily build and release process, ML pipelines for training and validation often do best when ran daily.

AWS even has a drag-and-drop pipeline designer that lets you quickly tweak the training process.

The resulting

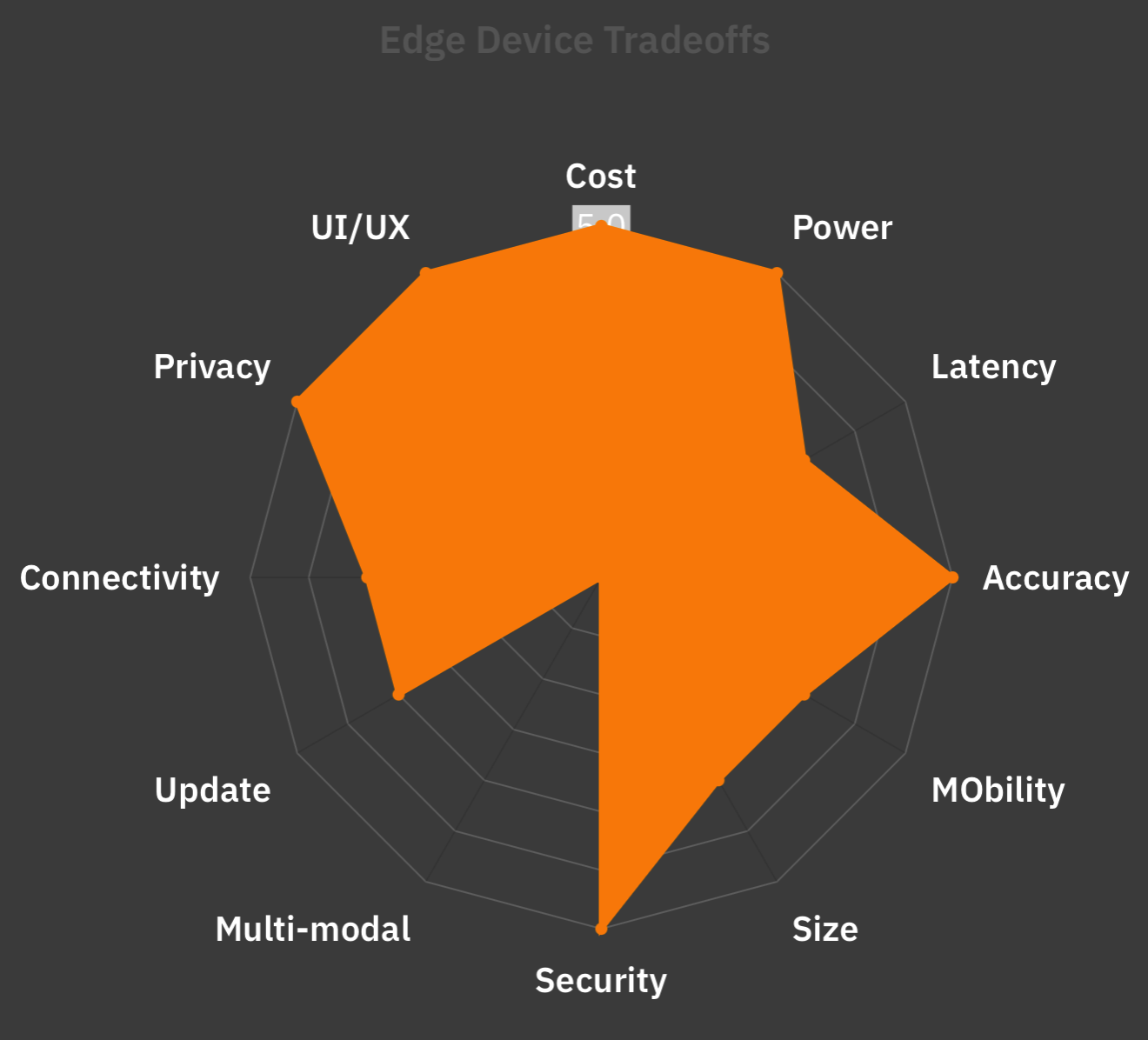

To run on a standalone device, the size of the model depends on the hardware’s capabilities. The larger the model, the more resources (RAM, storage, processing, and power) will be needed. This affects the device’s cost, the amount of heat it generates, the power it consumes, and its overall performance. There are many trade-offs.

It involves working within the envelope limits of current technology, economics, and usability. There is no perfect, single solution.

There is one constant, however:

Types of Hardware

The era of solid-state computing started with a Central Processing Unit (CPU). Early computers used the CPU to handle all I/O and processing. However, as advances such as terminals and color graphic displays emerged, it became clear that some of the work would need to be offloaded to a device dedicated to rendering. Enter the Graphic Processing Unit (GPU).

Advanced visualization algorithms (like CAD/CAM, CGI), or Fractal Geometry in terrain mapping and gaming required complex mathematics that could be run in parallel.

GPUs were custom-designed to handle those efficiently. Tools like AutoCAD, Pixar’s Renderman, or Bryce were used in the 1980s to push the frontiers of what could be generated by computers, leading to groundbreaking movies like

GPU designers created hardware that would allow multiple, parallel threads of execution. Software took advantage by hiding low-level tasks under libraries like OpenGL and DirectX. Over time, features like Ray Tracing and Radiosity required increases in parallel computation.

In 2006, NVidia introduced the GeForce 8 series cards, featuring a proprietary Compute Unified Device Architecture (CUDA) software library. In addition to support for graphics, CUDA allowed application developers to access low-level GPU instructions for use in their own applications, including non-graphic ones. This allowed computationally intensive operations to be sped up far beyond what could be done with plain CPUs.

It wasn’t long before general-purpose machine-learning libraries like Caffe, DLib, OpenNN, Theano, and Torch began taking advantage of this parallelism.

These were eventually followed by popular libraries commonly used today, including:

Custom Hardware

The price, power, and availability of GPUs have made them the standard for large-scale training, making the foremost commercial purveyors, such as Nvidia and AMD, highly valued companies.

GPUs are considered more general-purpose than custom hardware. But that hasn’t stopped well-funded companies from creating their own chipsets for training and inference:

| Company | Chip | Purpose | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alibaba | Hanguang | Inference | |

| Amazon | Trainium | Training | |

| Amazon | Inferentia | Inference | |

| Baidu | Kunlun | Training | |

| TPU v5p | Training | ||

| Trillium/v6e | Training | ||

| Ironwood | Inference | ||

| Huawei | Ascend | Training | |

| Meta | MTIA v2 | Both | |

| Microsoft | Azure Maia 100 | Training |

TPU

Underlying much of training and inference tasks is a large amount of vector processing and matrix multiplication. These can be abstracted into operations on mathematical constructs called Tensors.

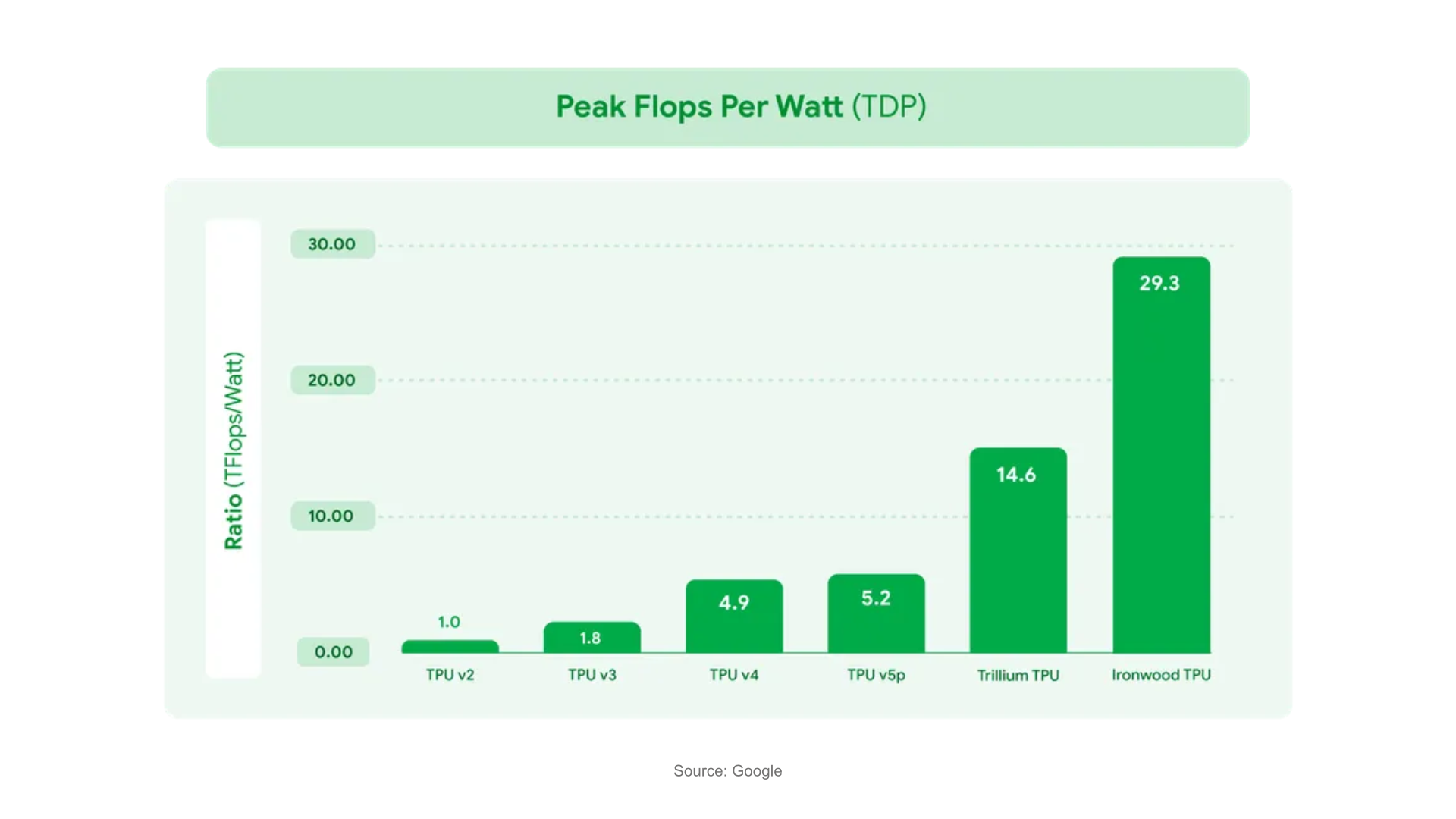

One way to perform these calculations quickly is by using parallel tasks on a GPU. Another is to perform Tensor operations on a custom-built, multi-core chip. This is the path Google has taken since 2015, by creating a custom Application-Specific Integrated Circuit (ASIC) chip. They call this a Tensor Processing Unit (TPU).

Popular software libraries like TensorFlow have been designed to make use of TPUs, if available, to accelerate operations.

Google has deployed large clusters of TPUs on their Google Cloud servers, and smaller, power-saving versions in their line of Pixel mobile phones. These perform on-device AI tasks such as image enhancement, Natural Language Processing, and custom inference.

The latest generation Ironwood TPU is designed to raise the bar for performance 10x from

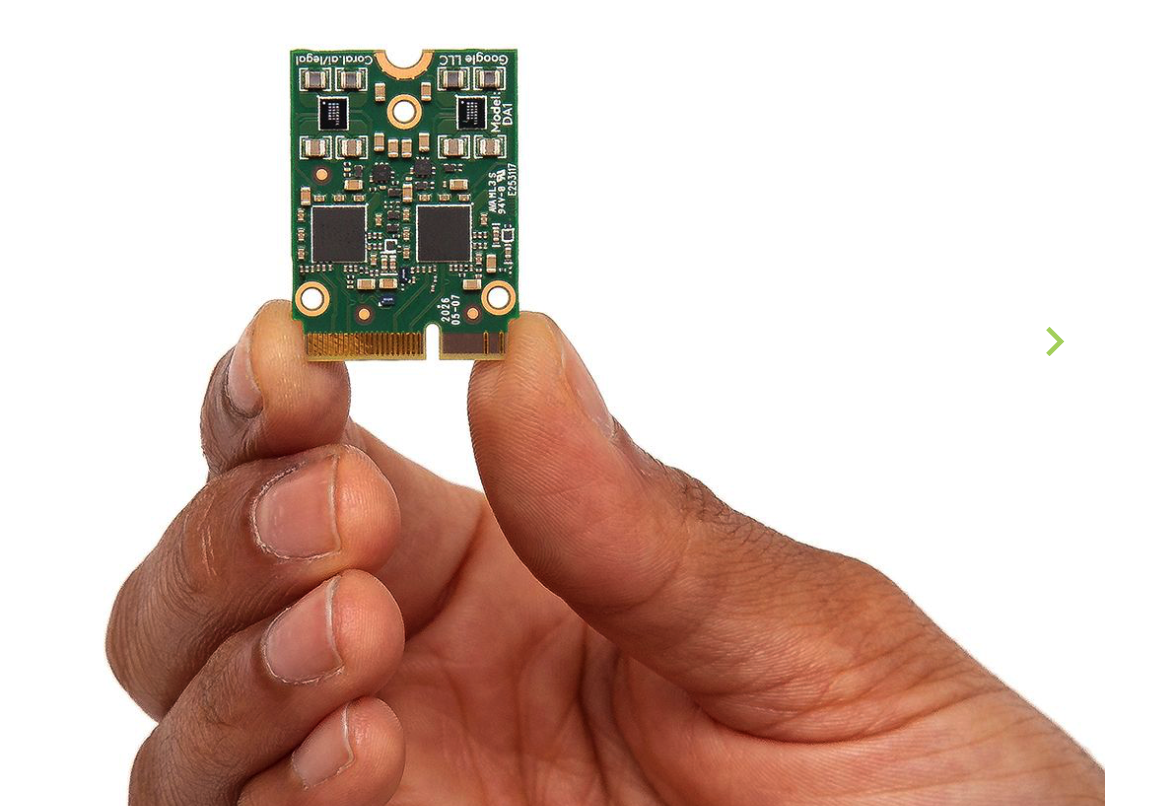

There are also lighter versions Edge TPUs available for embedded applications from Google subsidiary coral.ai.

A thinner version of TensorFlow called LiteRT (formerly known as TensorFlow Lite) is also available to run on ultra-lightweight embedded processors. These could be used in applications like in-camera object detection or natural language processing.

NPU

While TPUs operate at a Tensor level of abstraction, Neural Processing Units (NPUs) are designed to accelerate

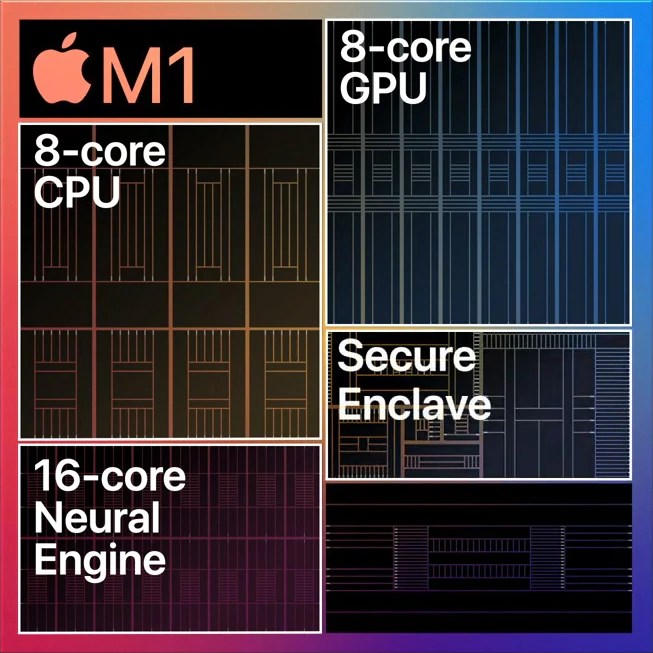

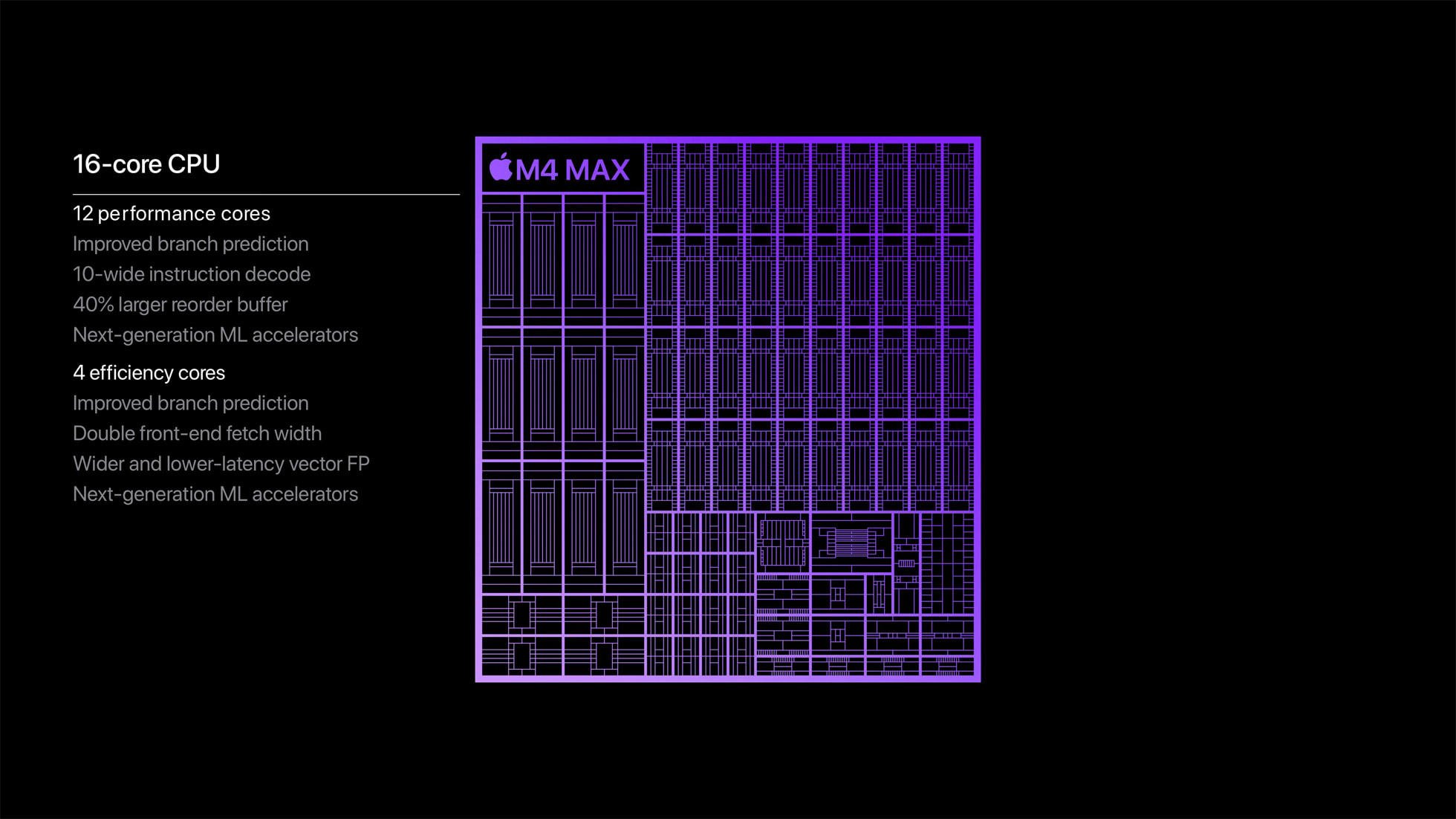

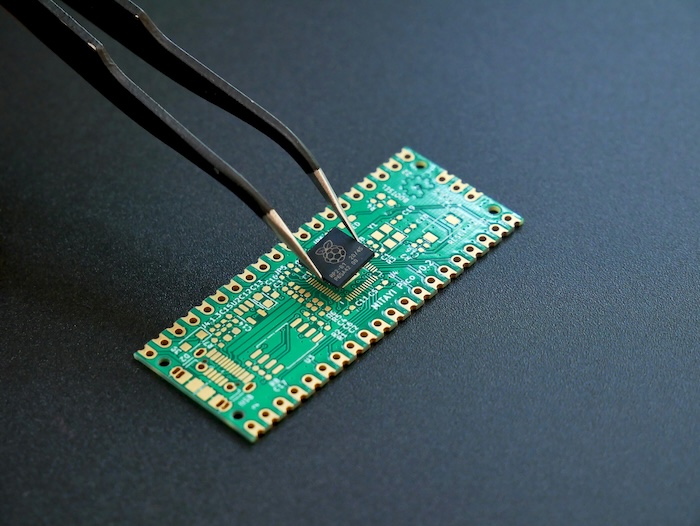

NPUs can also perform these tasks in parallel, but they can also be integrated inside System On a Chip (SoC) processors that are preferred for mobile devices. Here are a few examples:

- Apple Neural Engine, used in their A-series chips used in iPhones and iPads, and M-series chips used in laptops, servers, and high-end iPad Pros.

-

Qualcomm SnapDragon mobile processors. Qualcomm also offers NPUs in their Hexagon line of processors, as well as optimized for edge devices via their AI Hub Platform

-

Samsung has been including NPUs in their Exynos SoCs, targeted at AR and VR applications.

-

MediaTek, a popular supplier of processors, offers APUs (AI Processing Units) and NPUs as part of their Edge AI and mobile Dimensity processor line.

-

Intel has also been including NPUs in their Movidius Vision Processing Units (VPUs)

-

Huawei has Kirin NPUs built into their Ascend line of processors.

On the embedded device side, there are many manufacturers with built-in NPUs. These are primarily targeted at specific use cases, such as smart speakers, Appliances, Cameras with built-in object recognition, AR/VR, Automotive (driver assistance), Robotics, Smart TVs, Home Automation, and IoT.

Manufacturers include Allwinner, Amlogic, Espressif, Kneron, NXP, Renesas, and Sony

Custom

For highly-specific applications, like medical, military, aerospace, and satellite communications, it is possible to create purpose-built processors like ASICs and Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGA). These, however, are usually not designed for mass commercial applications.

ARM provides Silicon IP so its customers can create their own custom processors. It offers the Ethos NPU to help vendors create bespoke chipsets with built-in NPU support.

What’s the point?

The reason I catalog all these processors is to demonstrate the wide-ranging ecosystem that supports on-device AI processing. There is a gradual realization that on-device AI offers lower latency, better privacy, and reduced operating costs.

But having all these different processors creates several problems:

Fragmentation : the more specialized the processor, the more likely OS and application providers will need to create custom drivers, which creates inertia.

If running on Android, there used to be an NNAPI library, but it has been deprecated in favor of LiteRT which has support for Google TPUs and GPU delegates but not NPUs.

If on embedded devices, the most popular common platforms are FreeRTOS, Arduino, Embedded Linux, and WindRiver’s VxWorks.

FreeRTOS has no discernible support for AI devices. You could look into TinyML and NPU integration but the reality is you would have to add a fully-supported external NPU like the Ceva-NeuPro-Nano.

WindRiver recently announced integration with DEEPX NPUs, primarily targeted at Industrial applications.

On Arduino and [Embedded Linux]((https://www.sigarch.org/tiny-machine-learning-the-future-of-ml-is-tiny-and-bright/), the future points to TinyML EdgeAI.

-

Hardware Lag : creating custom processors, integrating them into devices, adding software support, and going into production takes time ranging from months to years. This means by the time a device is in a user’s hand, the technology has long moved on. -

Wrong Level of Abstraction : When it comes to hardware support for AI, you may be looking at using a GPU to detect shapes, or TPUs to edit images, NPUs to detect natural language phrases or run generative AI models. But general-purpose devices like smartwatches, phones, or AI-Assistants need to change and adapt to new technologies.

And if there’s one thing that’s certain, it’s the rapid rate of change.

Adaptive Hardware

Modular Design is not a new concept. From the IBM PC ISA Bus, to CPU Sockets and Fairphone Phones

What makes the concept challenging is:

1) Plug and Play: Standardized interfaces between the Main Device and the accessories. With hardware, there are other complexities such as Impedance Mismatch and Clock Timing.

2) Planned Obsolescence. Most hardware devices are purchased once and kept until they fail. A washer/dryer is a significant investment. They are kept until they physically fail or the electronics stop working.

3) Short-term Design. Manufacturers often create products and components for a single product or family. Carmakers realized that this would increase costs, complexity, time to market, and maintenance costs. So they came up with Modular Manufacturing Platforms. This allowed them to share common components across a range of vehicles. It also helped with innovation because it allowed them to standardize on commodity parts, which allowed them to focus on what made their products unique.

Extensible Platforms

An Automotive Platform isn’t just a headlamp or a seatbelt:

At its most basic level, an automotive platform can be described as

“the sum of all non-styling specific parts – functions, components, systems, and sub-assemblies – of a vehicle.”

Much like the ideas we covered in the section on Extensions, multi-function hardware extensions require a process for

A well-known example of such a platform is the Universal Serial Bus (USB), to which the Model Context Processor spec likes to compare itself:

MCP is an open protocol that standardizes how applications provide context to LLMs. Think of MCP like a USB-C port for AI applications. Just as USB-C offers a standardized way to connect your devices to various peripherals and accessories, MCP provides a standardized way to connect AI models to different data sources and tools.

This is a mantle picked up by many:

- MCP: The new “USB-C for AI” that’s bringing fierce rivals together

- Model Context Protocol (MCP): The USB-C of AI Data Connectivity

- Everything you need to get up and running with MCP – Anthropic’s USB-C for AI

Unfortunately, the analogy falls apart if you actually talk to hardware people.

As facile as it may be, let’s dig into the USB-C analogy.

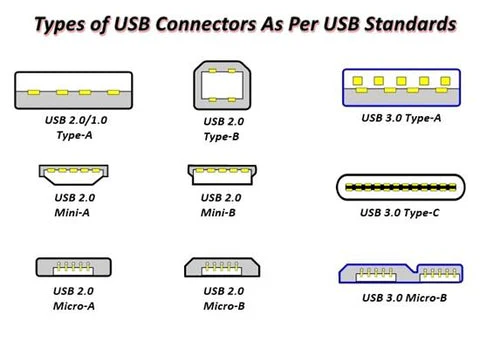

USB itself went through several variations:

And it had to go through some well-deserved ribbing before settling on the double-sided USB-C design:

Even still:

Although they all come in the form of USB Type-C, due to the differences in protocol versions and speeds, the matching of the system, device, and USB Type-C cable must be consistent to achieve the best performance, while different devices or systems require different cables. Taking just speed as an example, USB Type-C cables have the following variants:

The USB Spec is a complex beast, mainly due to its insistence on backward compatibility.

Once a new device is plugged in, there are a sequence of events where the main system and the USB device go through a number of communication stages, exchanging

# Side NoteFeel free to skip this if it’s too much.

The reason I’m going into this much detail on USB is to illustrate that the stages it goes through are analogous to how AI systems like MCP are not sufficiently developed to handle what will be needed for truly plug and play AI components.

These are lessons that we should have already learned. We’re not here for a USB tutorial. In the back of your mind, I want you to consider how each of these USB stages directly apply to the AI/software world.

MCP is not like USB-C. Not really.

But it can be.

Once a USB device is plugged in, the two devices (which may not have previously met) need to establish how they will communicate. At some point, the host undergoes a process called Enumeration. This allows the device to transmit a series of descriptors that identify its capabilities, enabling the host system to configure itself properly.

This is the magic you see when you plug a new device into your laptop for the first time. Once the host connects to the peripheral device,

Device Descriptor : contains information such as serial number, vendor, and product IDs. It also contains the class of device (remember Taxonomies), which the host can use to decide which device driver to load. If it doesn’t have an appropriate one, it can try to look on the web or ask the user to download and install one. Standard device classes include the HID (Human Interface Device) class, which encompasses devices such as mice, keyboards, and joysticks, and the Mass Storage class, which covers removable storage devices. If a device doesn’t fit into any of these, it likely requires a custom driver.Configuration Descriptor : this defines how the device is powered, how much it requires to use, and what interfaces are available. This allows the host to inform the user if the device requires an external power source and to prevent physical damage to the host by drawing excessive power.Interface Descriptor : Allows support for devices with multiple interfaces. The host can then decide which ones would work best for what it needs.Endpoint Descriptor : This specifies data bandwidth, transfer type, and the direction of data exchange as a source (IN) or a sink (OUT).String Descriptor : This is the human-readable data, including product and manufacturer name and the serial number.

Once the host system has processed all these descriptors and gone through the device driver matching process, the device is now ready for use. From now on, each time you plug in the device, It Should Just Work.

Except that the host system undergoes this workflow every time a device is plugged in, and validates that the device is still compatible and all the necessary host-side components are in place. If any of these conditions are not true (for example, if the operating system has been upgraded, or a malfunctioning device has been replaced with a similar model), there is an opportunity to re-validate.

# Side NoteOne stage a USB device does not have, which component architecture (like MCP) should have, is the calculation of runtime operating costs. USB devices do not incur a cost for use. MCP servers do, in the currency of tokens or via different payment schemes as discussed before, such as subscriptions.

Security

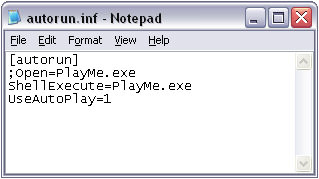

What if someone walks up and plugs a USB device into your computer? On most computers, the device will be accepted. On Windows machines (unless explicitly blocked by corporate policy) any software on it can automatically run. All you need to do is create a file in the root directory of a USB drive and call it autorun.inf with a few lines of text:

For fans of Mr. Robot TV show, you can try a Rubber Ducky. A USB device that also simulates keyboard events. Plug one in and have it quickly extract data from a target system.

Or just go for maximal damage and plug a USBKill device to electrically overload and zap the motherboard.

I know we’re driving the USB/MCP analogy into a ditch, but the USB interaction with a host has many unintended consequences, including that of trusting devices unquestioningly. The USB-IF Authentication specification provides a lightweight attestation framework, but support is not required by all vendors. The only other line of safety is obtaining a Vendor ID from the USB forum, but that mainly requires providing an address and paying a $6K fee.

Other device certification systems do have stronger enforcement mechanisms:

-

Apple’s MFi Program: requires registration, vendor validation, and manufacturing at approved facilities.

-

Matter’s Attestation Certification Process is much more robust in avoiding fake devices or malicious providers to participate in the ecosystem.

These programs intentionally get in the way of innovation and just hacking something together, in order to create a trusted environment for consumers. It is easy to dismiss them as bureacracy and overhead. But we’ve seen what happens when there is nothing in place or it is not enforced.

The point is, we should be careful giving hardware systems (like AI Assistants or accessories) unfettered access to private user data. Attestation frameworks are a starting point.

Maintenance

Devices are physical objects, and these eventually break. That’s just physics.

Connected devices are unique in that they can send signals on their own internal health to a server. And if they fail to send a status message at regular intervals (i.e.

For more complex devices, there can even be internal sensors to monitor the health of the device and use that to pre-emptively detect anomalies. For example, if the temperature or humidity inside the box gets too high. If there is a microphone, if the sound of a motor or compressor exceeds a certain level, that could be a sign of impending failure.

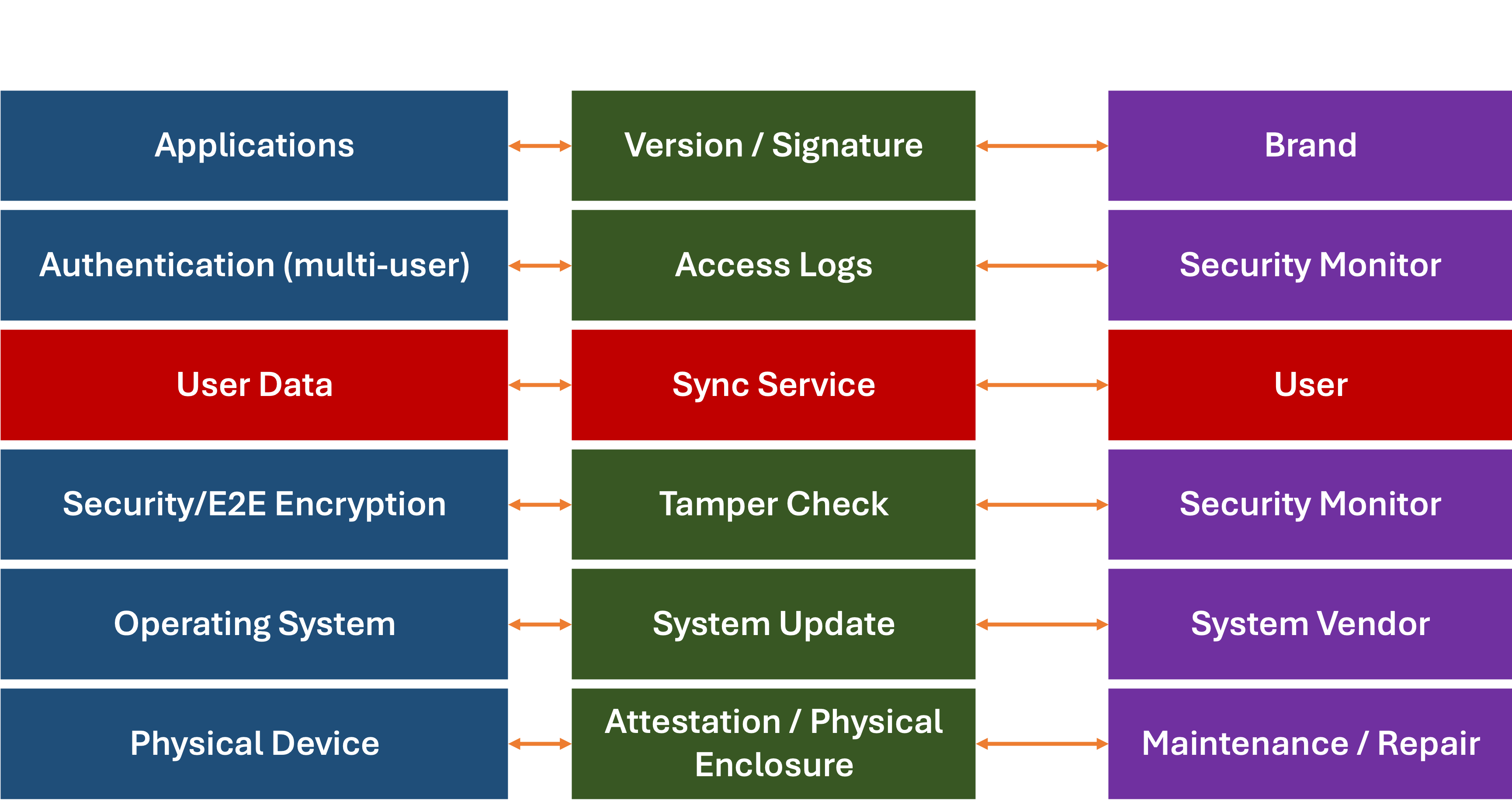

This data can be sent to a separate maintenance monitoring service, without violating a user’s privacy, by maintaining a layered communication architecture:

For each part of the system, the monitoring and support data can be sent to a separate service, without violating user privacy. This same architecture could be applied to both software and hardware services.

Adaptive AI

Let’s recap:

-

On-device processing offers many advantages (performance, latency, cost) over cloud-based AI.

- We’ve gone from CPUs to GPUs, TPUs, and NPUs. Each has tackled a different level of abstraction and helped speed up a particular function (matrix operations, tensors, and neural networks). The next generation will likely handle a different level of abstraction. The lesson here is:

things will change . - Hardware, unlike software, can not be easily updated.

Software is fungible. Hardware isn't. You can update the firmware or even microcode on hardware, but at some point, you are limited by the physical domain. -

Modular Design systems (at scale) have helped save a lot of time, sweat, and money.

- The USB system has gone through a lot of variations, but at its core, it allows a variety of known and as-yet-unknown devices to be

plugged in and out of host systems. -

Maintenance is a key advantage of a smart device, especially if it is pre-emptive so problems can be fixed before they occur.

I’ll add one last one:

Let’s put these all together. The one logical conclusion is that for on-device AI-based hardware to work, it needs to be:

- Modular

- Support self-discovery

- Easily updatable

- (Violating the Rule of Three) self-monitoring, and

- Cost-Effective

# Side NoteI have been thinking about the design of just such a thing for the last 20 years.

For some reason, nobody has been willing to take a stab at it. If anyone reading this far has a decent budget (hardware is expensive, yo!), feel free to get in touch.

Title Photo by Adrien Antal on Unsplash