User Data

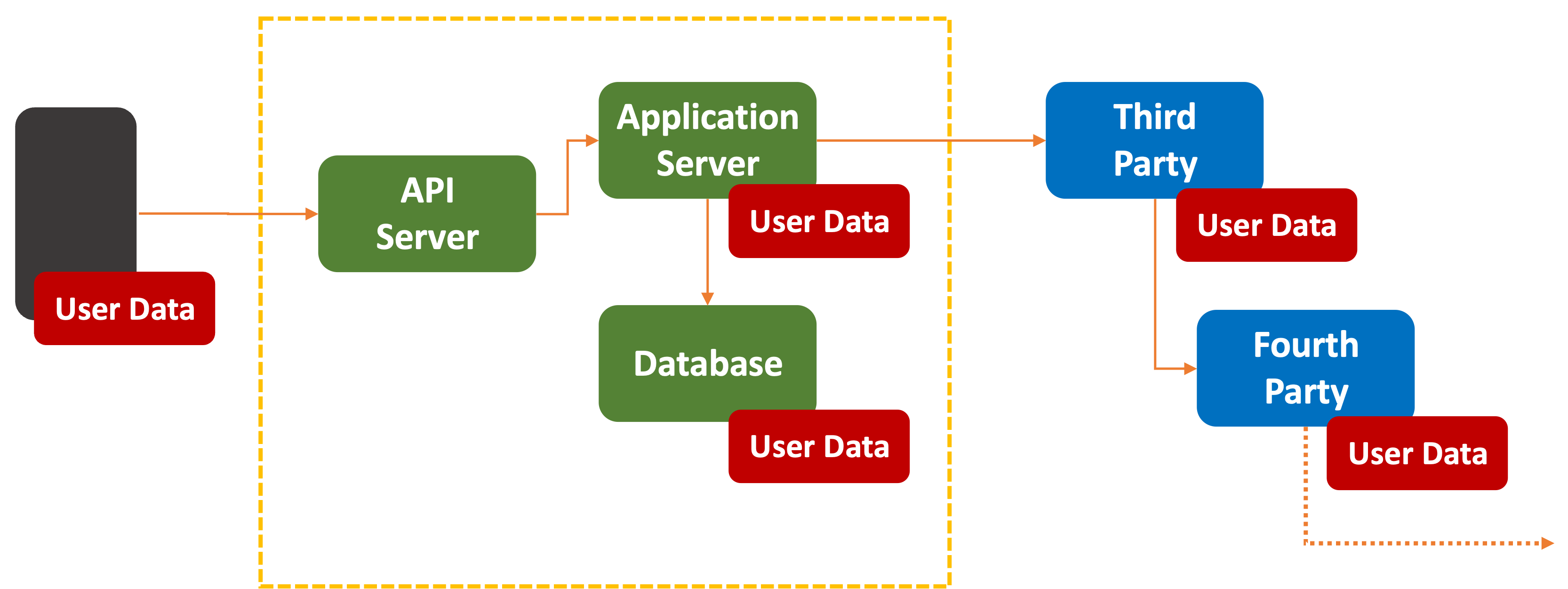

When you give access to your private data to an AI Assistant, where does it keep your data and who has access to it?

Your private data could be anywhere, from your phone, AI Assistant, vendor cloud software, or any service that software relies on.

In the research paper How To Think About End-To-End Encryption and AI: Training, Processing, Disclosure, and Consent, there are serious concerns raised about implications of privacy when it comes to AI interactions:

While they originally served as standalone applications, AI models are now increasingly incorporated into other everyday applications and throughout devices, including messaging applications,

in the form of AI “assistants.” Interacting with these assistants is often baked into the user experience by default, made readily available as part of the application client (e.g., within a messaging app).Such integration creates new systemic data flows at scale between previously separate systems , and accordingly raises security and privacy considerations not limited to E2EE.

One of their key recommendations?

Prioritize

endpoint-local processing where possible.

In other words, run local. The less sent out to the cloud, the better. We’ll cover this more in the next section.

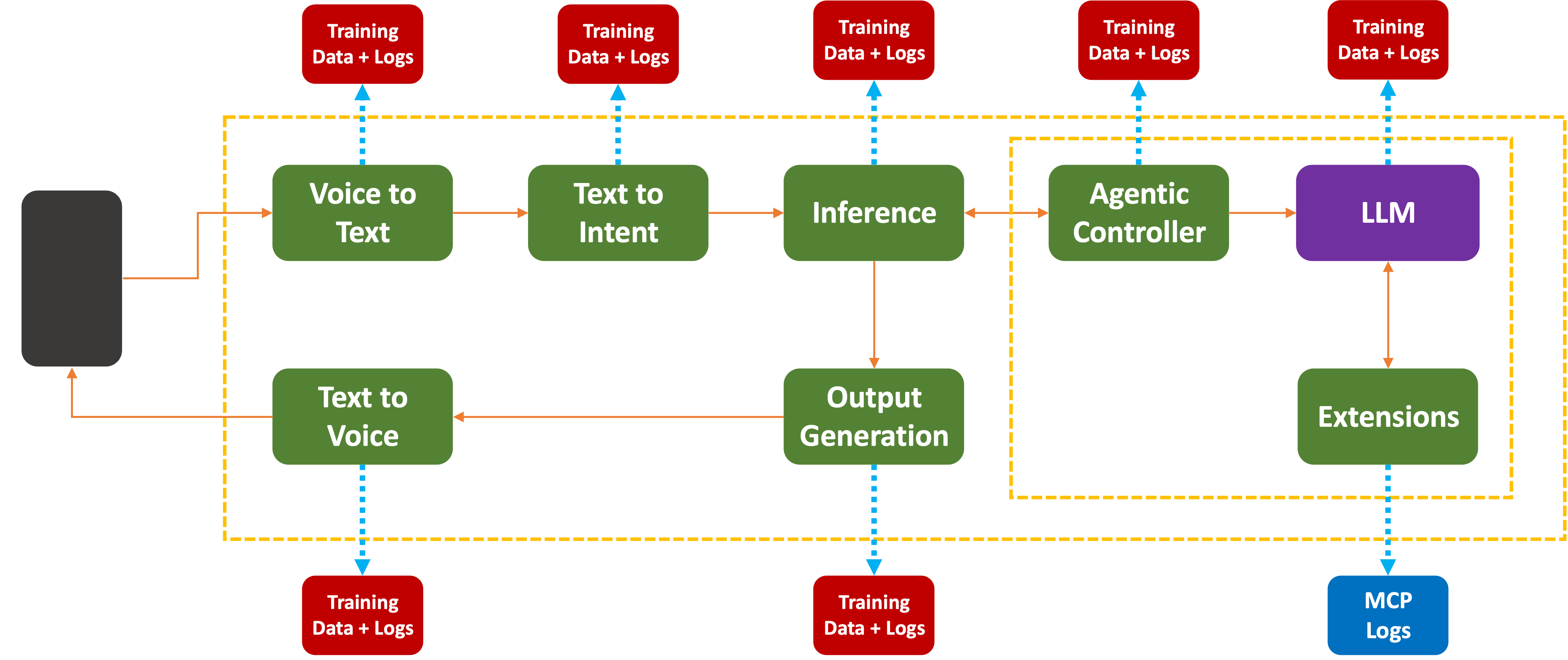

Siphoning Off

Every stage of an AI Assistant’s inference pipeline has been trained using previously obtained data. Where the data comes from is out of scope here. But a great source of fresh new data flows into every inference engine in the form of

The data could be in the form of raw data, log files, or detailed telemetry on the underlying infrastructure.

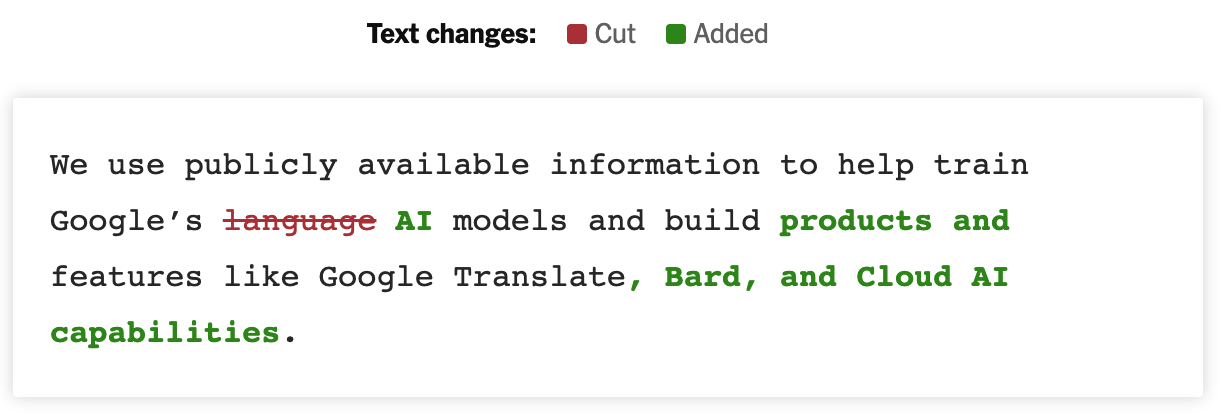

Even if the company swears in their End-User License Agreement that no user or company data is going to be used for training purposes, I promise you logs are being kept. There is a point after which the training data’s low-hanging fruit has been picked. We now see efforts to make AI companies actually pay for getting access to more training data:

What would you do if you had a large and growing pot of data sitting on your servers?

It’s just there, begging to be used…

This is just Google. The article covers other changes in terms and conditions from Adobe, Snap, and X. Many others did not have to make a change. Access was already granted when users signed up and accpeted the fine-print.

So What?

For most of us, our sense of online privacy lies somewhere on the range from:

To:

With an occasional:

Many companies state that user data is

This often means that a long Universally Unique Identifier (UUID) (also called Globally Unique Identifier (GUID)) is generated for each user when they first register for a service. From then on, every user record is tagged with that UUID value.

The PII data is stored separately from non-PII data, with the UUID acting as the connective tissue. The idea is that if someone hacked into a records system, or sniffed the data in transit, they would

The other problem is that it is relatively easy for third-parties to track user interactions without having to break into any databases. For that, we have

Digital Fingerprinting

When Apple opened iPhones to third-party app development, they very generously provided a Universal Device Identifier (UDID) to help developers keep track of what device was connecting to their services.

This was (as you might imagine) almost immediately abused for tracking and logging purposes.

By 2013, Apple realized this and ordered all applications to remove access to the function they had provided themselves for this purpose.

# Side NoteAndroid also established a similar restriction even though it took until Android 10 before access to the unique ID was blocked. It’s still there, mind you, but you need to have access that is not too hard to obtain:

Android 10 (API level 29) adds restrictions for non-resettable identifiers, which include both IMEI and serial number. Your app must be a device or profile owner app, have special carrier permissions, or have the READ_PRIVILEGED_PHONE_STATE privileged permission in order to access these identifiers.

That bit about the profile owner means any work-supplied phone with MDM can easily access that data.

The problem was that software developers still wanted to collect usage analytics and disambiguate one device from another. Thus, Apple and third parties began a cat-and-mouse game to find ways around this problem.

Enter Device Fingerprinting:

A device fingerprint or machine fingerprint is a calculated identifier used to identify a remote computing device based on collected information about its software and hardware. Robust fingerprints are based on a wide range of telemetry, including data points such as:

- Hardware, including screen properties, graphics card and RAM

- Graphics, including supported video codecs and canvas properties

- Audio properties and codecs

- Environment factors such as OS, connectivity, and storage

In fact, many other factors can be considered when trying to uniquely identify a device. Since most phones and tablets are single-user devices, that device essentially points at a single person.

Want to see for yourself? Go check out Am I Unique, or see how trackers view your browser via Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Cover Your Tracks.

You’ll love it!

There is a Better Way

Before you panic, realize that there is a simple solution to all this:

But that means you will lose all the promised benefits and advances. Besides, if you’ve read so far, there’s a good chance you’re not here for that kind of advice. Besides, you may not have much choice once the enterprises you work with embed them inside their services.

The problem that needs to be solved is

It turns out that Apple came up with the starting point of such as system. They called it Local Differential Privacy:

Local differential privacy guarantees that it is difficult to determine whether a certain user contributed to the computation of an aggregate by adding slightly biased noise to the data that is shared with Apple.

Applying this globally to

For example, the amount of RAM or the size of the screen in pixels on a phone is not upgradable. That, however, can change on a desktop or laptop. On a phone, the more static the information, the more jitter needs to be added to the device data. Changing how many pixels a browser supports is one reason applications or browsers ask for that information. But instead of returning the raw data, an on-device subsystem could easily return a

What’s more, the browser model where Javascript requests device data could be inverted so instead of a script

This approach does not allow system data to leak out to Digital Fingerprinting routines. There is a precedent for this: Apple and Google stopping applications from asking for

They can do it again.

A More Perfect Union

Traditionally there has been a clear boundary between what is considered

The same model applies to more recent operating systems, like Windows, MacOS, iOS, or Android.

This bifurcation is there because a system’s scarce RAM has been a scarce resource shared between individual services and operating systems. Memory, files, and processes are given access to System or User regions depending on whether they need access to those features.

Most of these operating systems also define fine-grain permissions, to allow users to decide whether an application should get access to a resource.

# Side Note

<soapbox>Asking users to decide whether an application should access resources like Files, GPS, camera, or notifications before the user has actually gotten into an application and made use of it must be the

single, stupidest, most idiotic user experience pattern in the history of computing.Whoever thinks this is a good idea needs to learn about Bruce Schneier’s Security Theater

</soapbox>

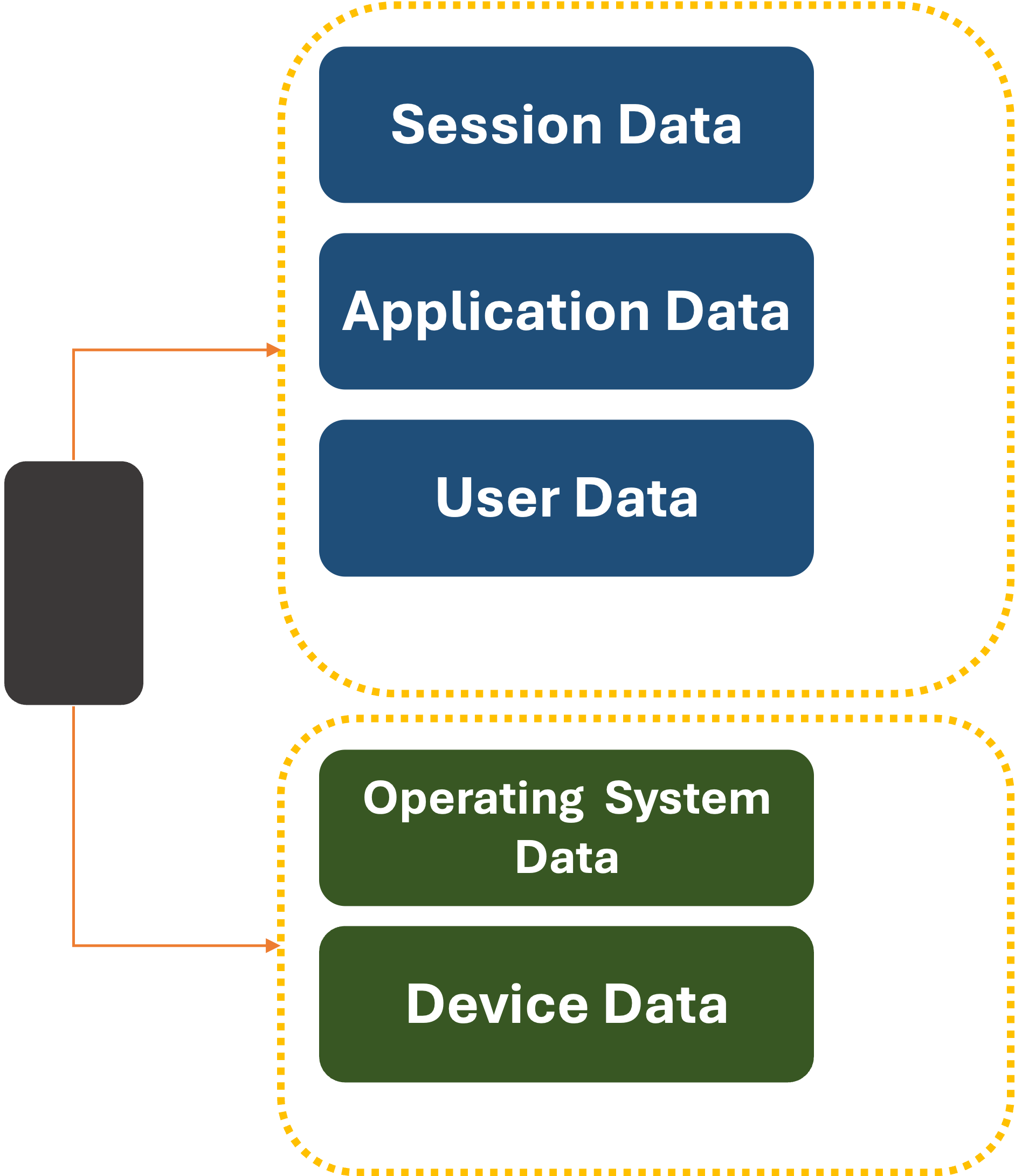

At a very, very high-level, this is what an app view of the world looks like:

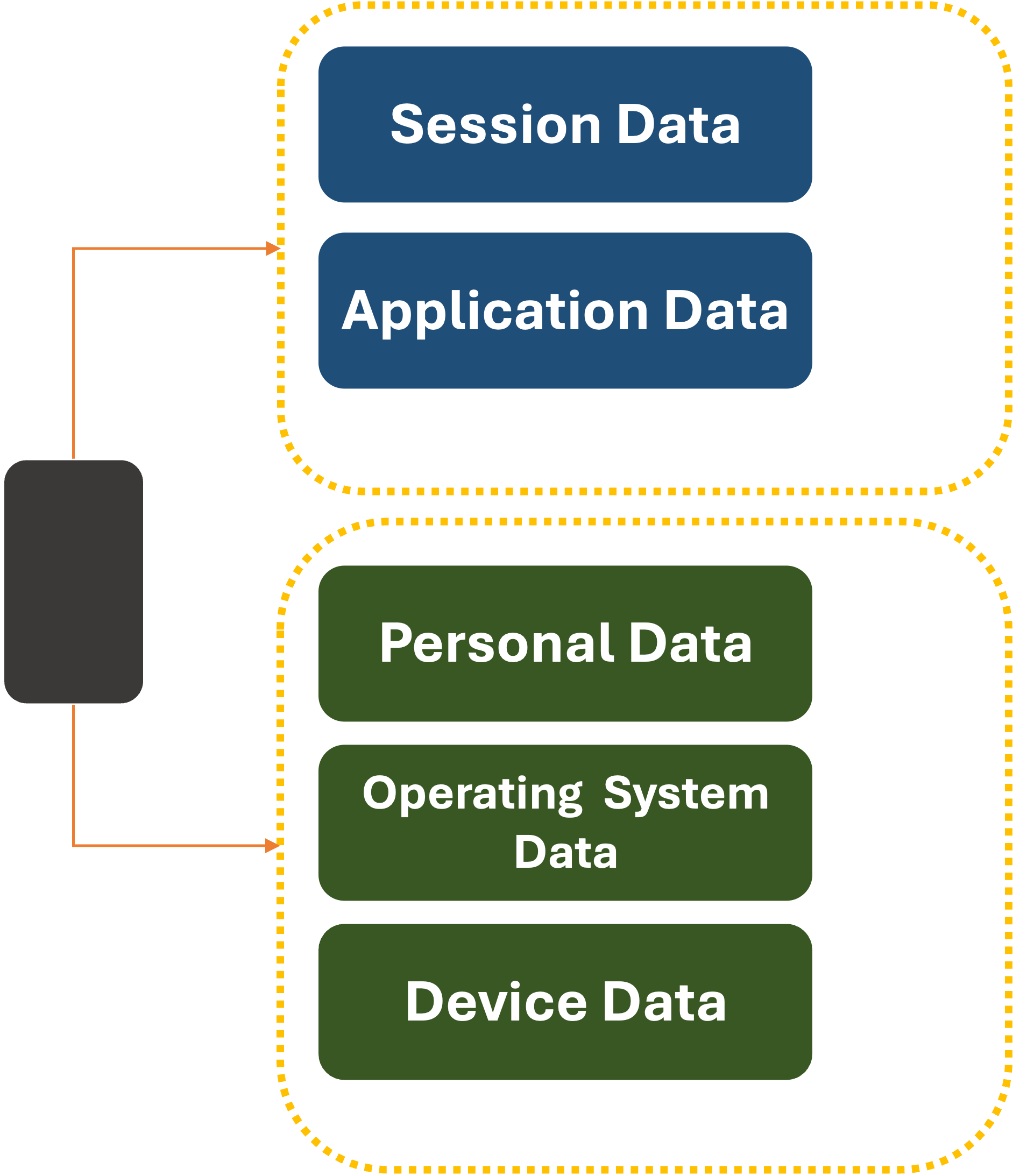

What if we changed it only slightly:

Now, the

What’s more, the system can vend out temporary UDID values on a per-item basis for individual applications. Websites that want to register a new user would be given an opaque, unique UDID by the system. What’s more, the system could rotate this value periodically to prevent third or fourth-party data leakage.

The same principal as Apple’s

‘But what if I lose my device, upgrade it, or need to run an app across different devices?’ you might say.

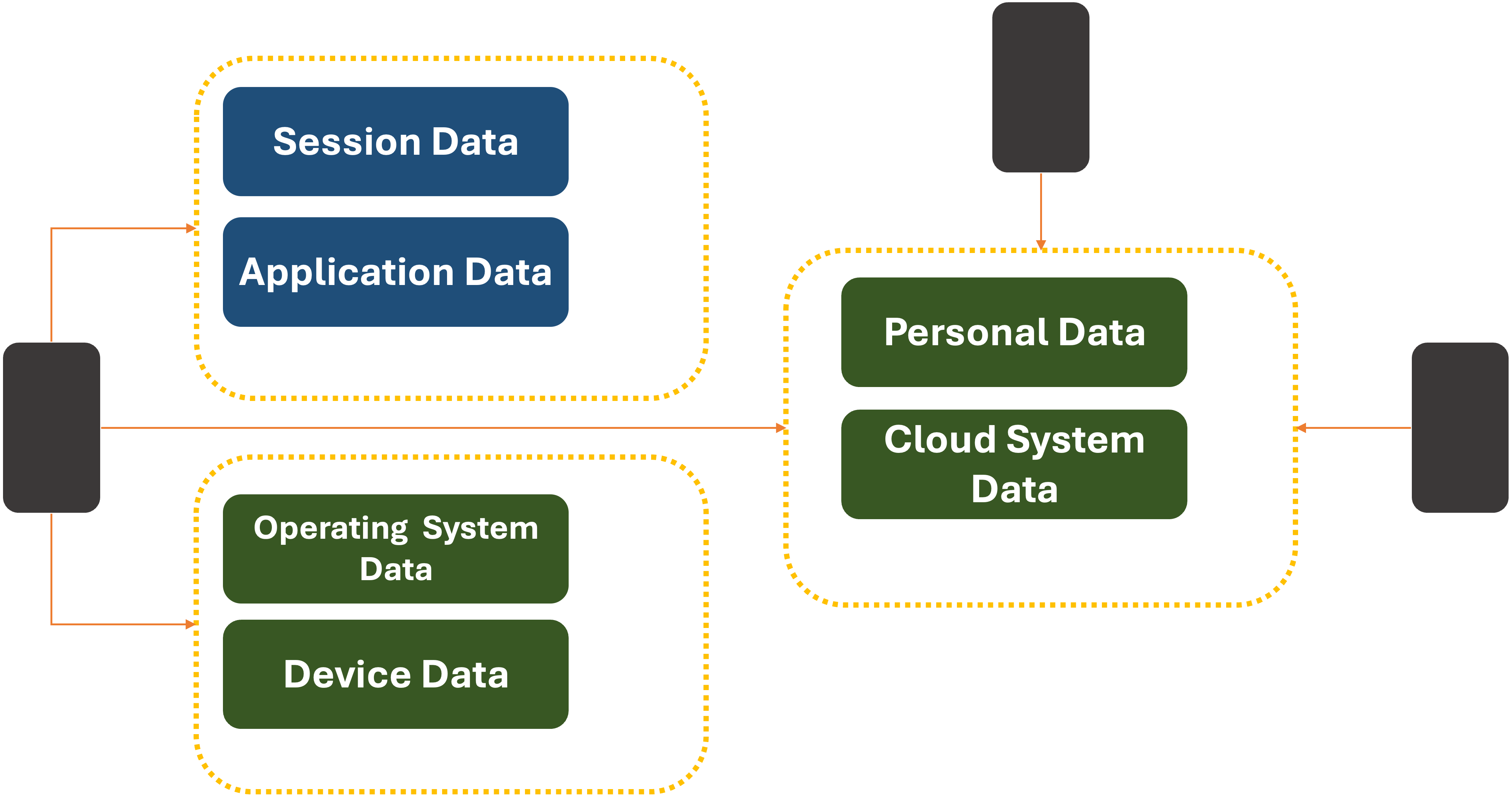

Fortunately, that is a solved problem. Today, when you use an Apple or Android device, your System data is shared between devices via a

Backup data is currently end-to-end encrypted so it can only be saved and restored. But

We currently trust a significant amount of our digital lives to these providers. Giving them access to more personal data is not a big stretch. But if doing so is outside someone’s comfort zone, third-party

This would also help mitigate risks of violating regional Data Sovereignty rules.

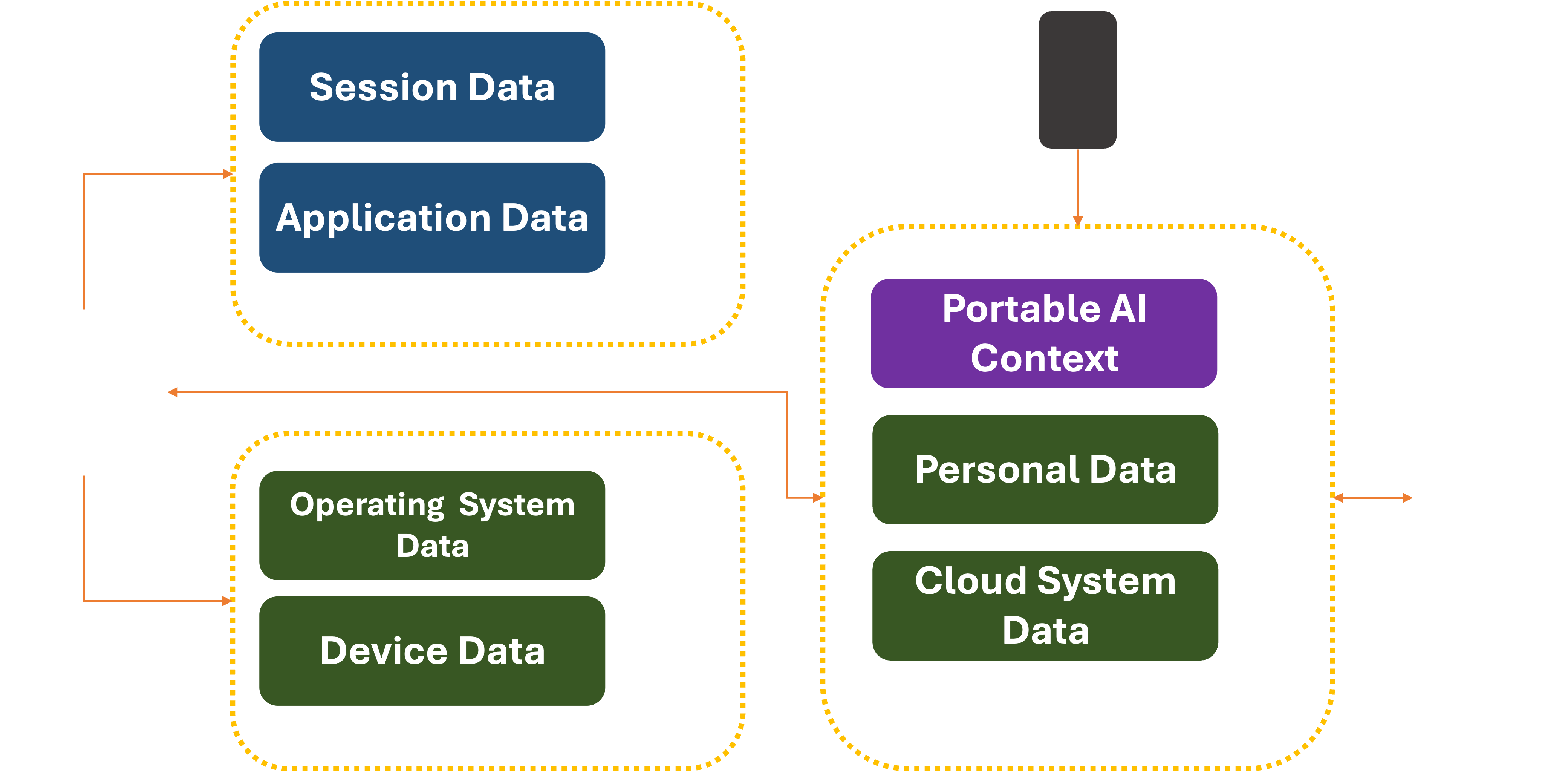

There is an evolutionary path for data if we expect to have our assistant with us wherever we go. That is to store a

Companies like Alibaba, Apple, Google, and Microsoft will no doubt try to be the first to lay claim to this data and integrate it tightly into their offerings. Or the functionality could be created and open-sourced by a standards body before any single commercial entity lays claims to it. In either case, the security of the data would need to be guaranteed via End-To-End encryption, backed by Hardware Security Modules rotating the keys frequently.

Closing Thought

When it comes to AI Assistants, the gold standard will be keeping personal data inside

The systems that manage access to this data can scrub the PII before they leave your devices.

To do this properly, they would likely need help from the hardware. That comes next…

P.S. Don’t forget to give EFF a donation. They do good work.

Title Photo by Piotr Musioł on Unsplash