Industrial Automation

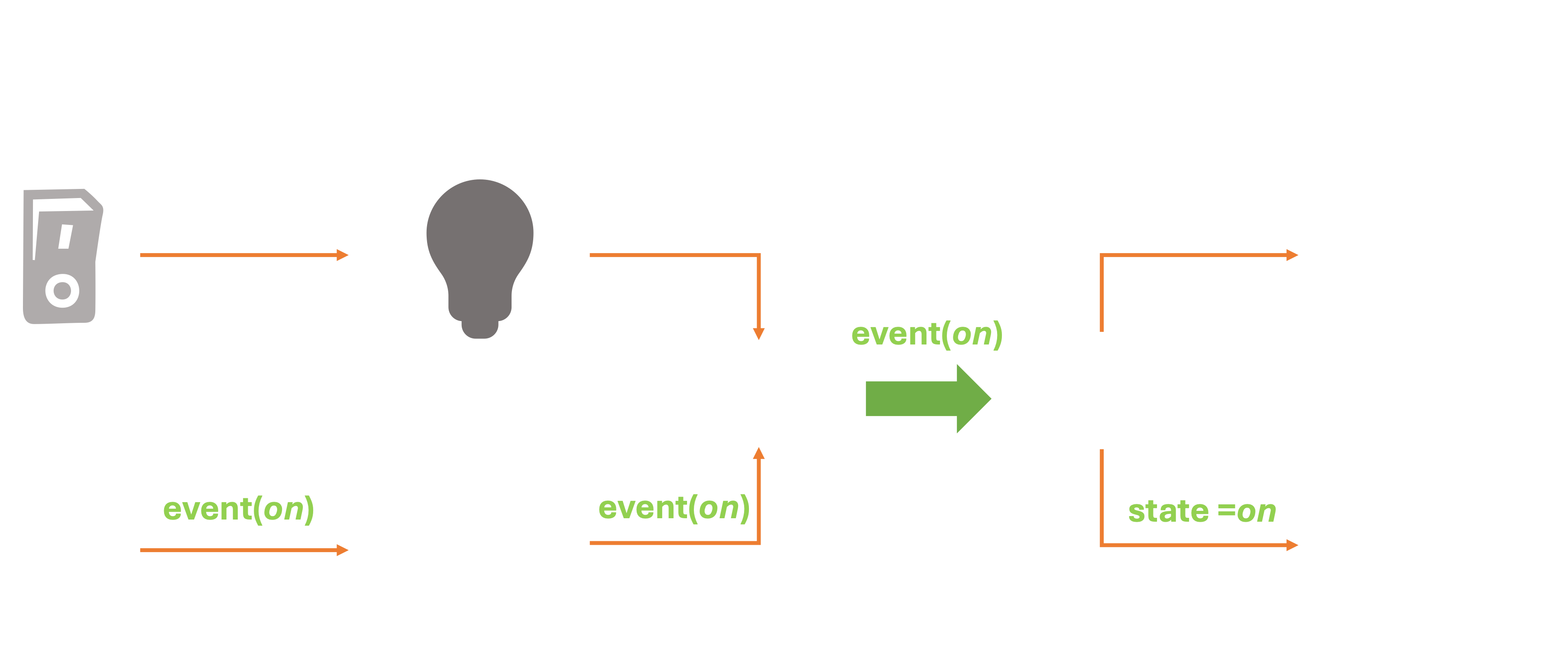

When physical devices were first connected to the digital/virtual world, it was simple to see the relationship. The state of a physical light bulb can be easily represented as an on/off toggle in the digital world.

This provides a clear, concise analogy that everyone can understand. If the light is on, the system assigns it a value, such as True, Yes, or 1. And when it is off, the state is transmitted to the digital world, and the value is changed to False, No, or 0.

But let’s unpack what I just said. When the state of the light changes, it is transmitted to the virtual world. How is the state detected, how is it changed, how is that analog state converted to a digital representation, and how (and when) is that state sent to the digital universe?

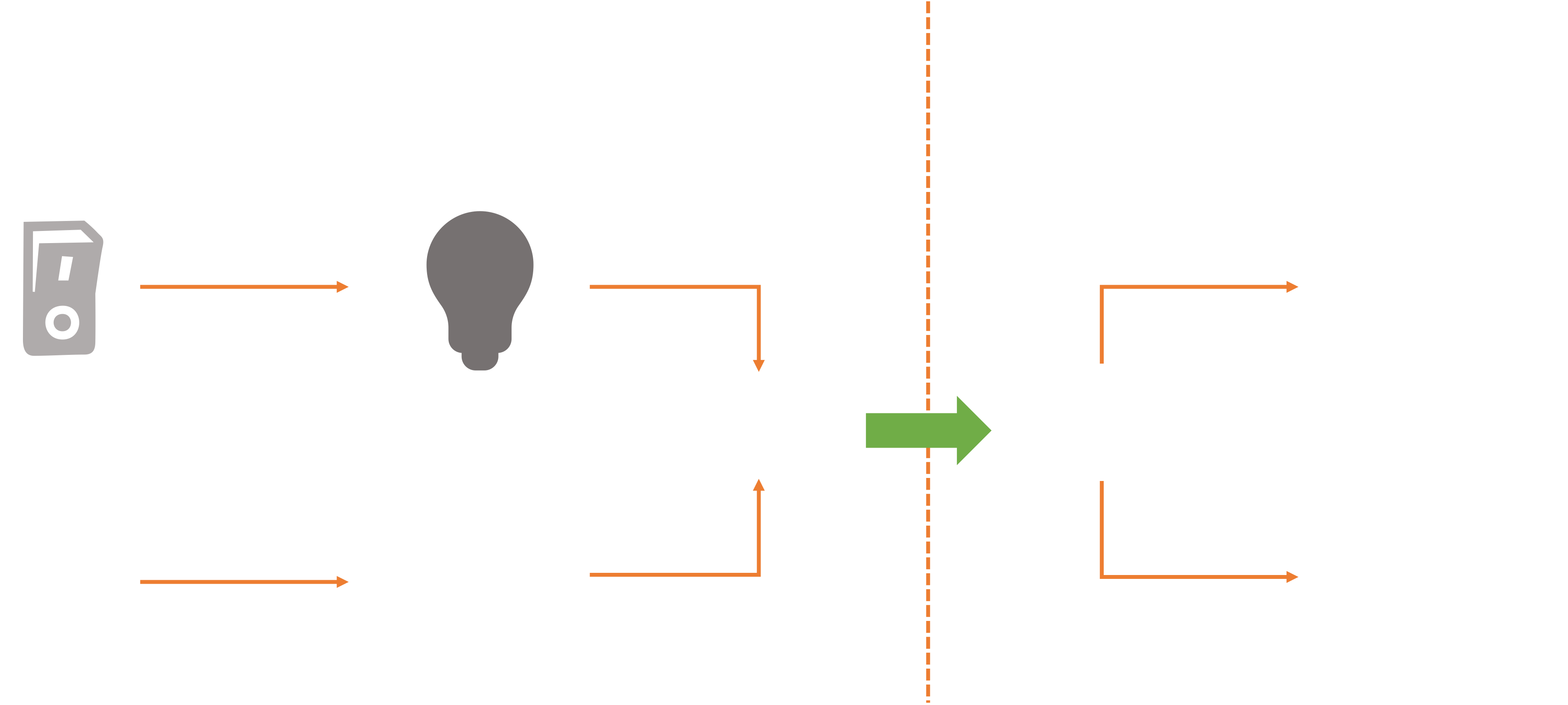

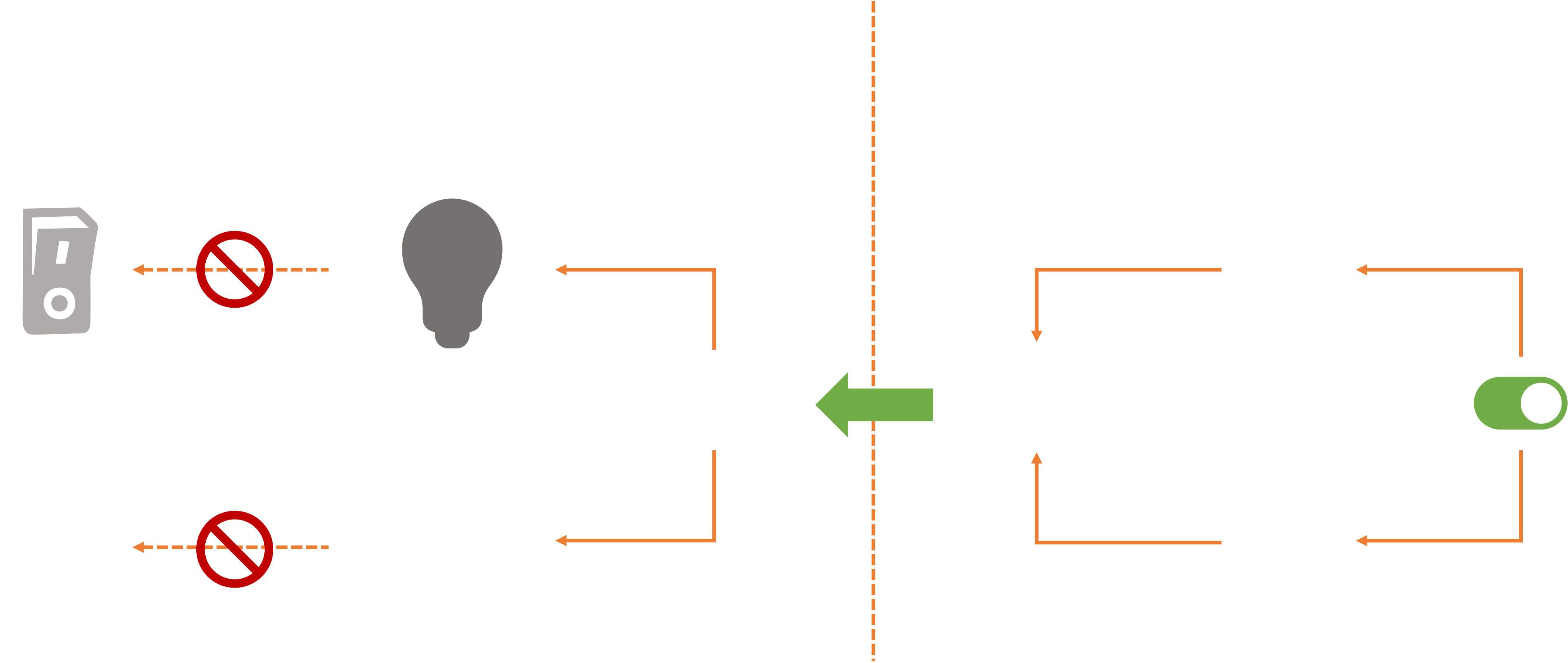

In reality, the diagram may look more like this.

A physical switch may be used to toggle the light on and off. A sensor detects the state change, converts it to a digital form, and sends it to a server or application, where the light state is updated.

Looks pretty good, no? We’re done.

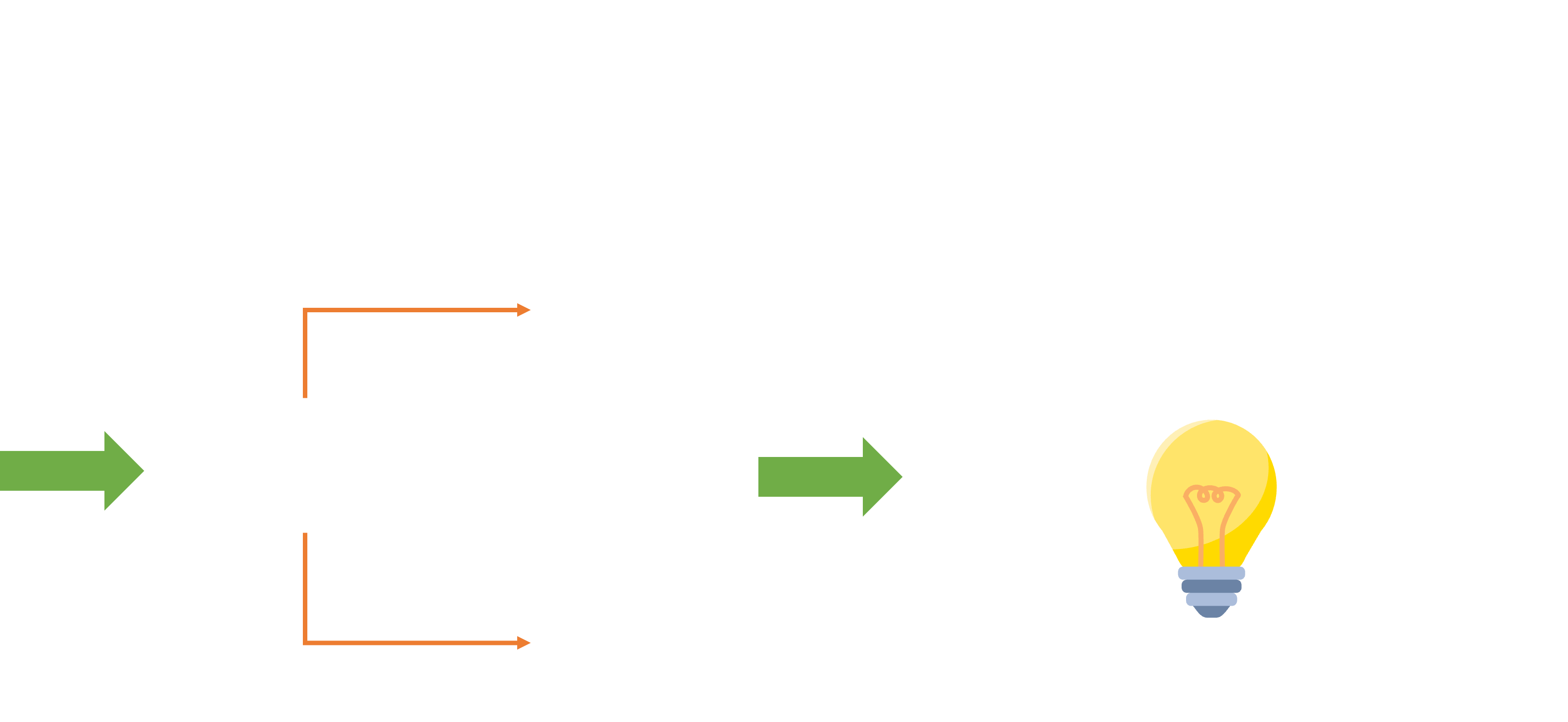

One of the advantages of this model is that you don’t have to constantly poll the state of the physical light bulb. That seems awfully wasteful. Most of the time, lights are in one state or the other, so the answer to the polling that comes back is going to be same.

As an optimization, we can have the Physical device only send an event when the state changes (someone flips the switch). This generates an event that can then be transmitted to the Digital store on demand, saving a significant amount of energy, bandwidth, and processing power.

Each time the dashboard receives an event, it is updated. It doesn’t need to go all the way back to the physical device, and it doesn’t need to keep re-drawing the bulb. We examine the Digital Representation, which displays the last known state of the physical device.

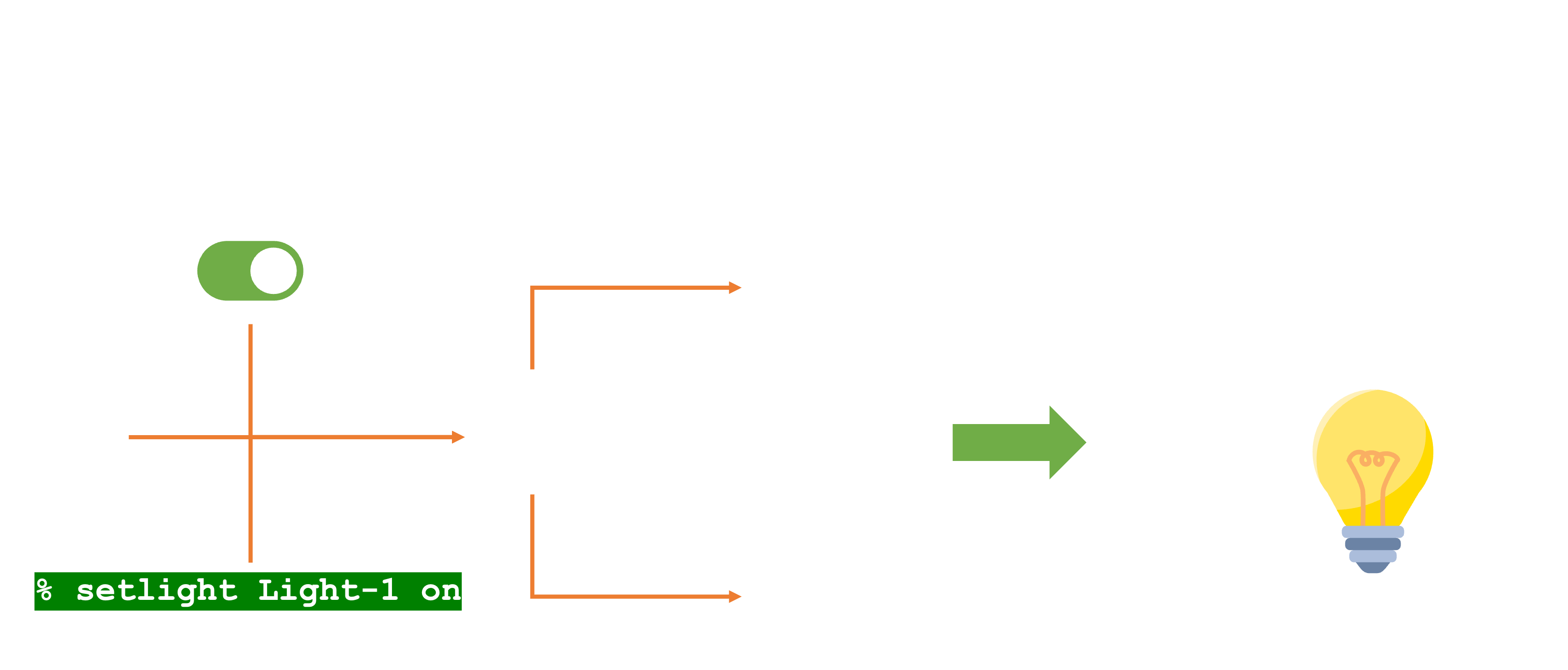

What’s even better is that we can activate, simulate, and test the state of this physical device using software in various modes. We’re no longer limited to a physical light switch anymore.

You might say we’ve decoupled the actions of the physical world from the operation of the physical world itself.

And since the system can be bi-directional, hey, cool, we can also go the other way! Toggling the light state in the Digital World can change the state of the physical bulb. That’s Power!

We got this nailed!

Except…

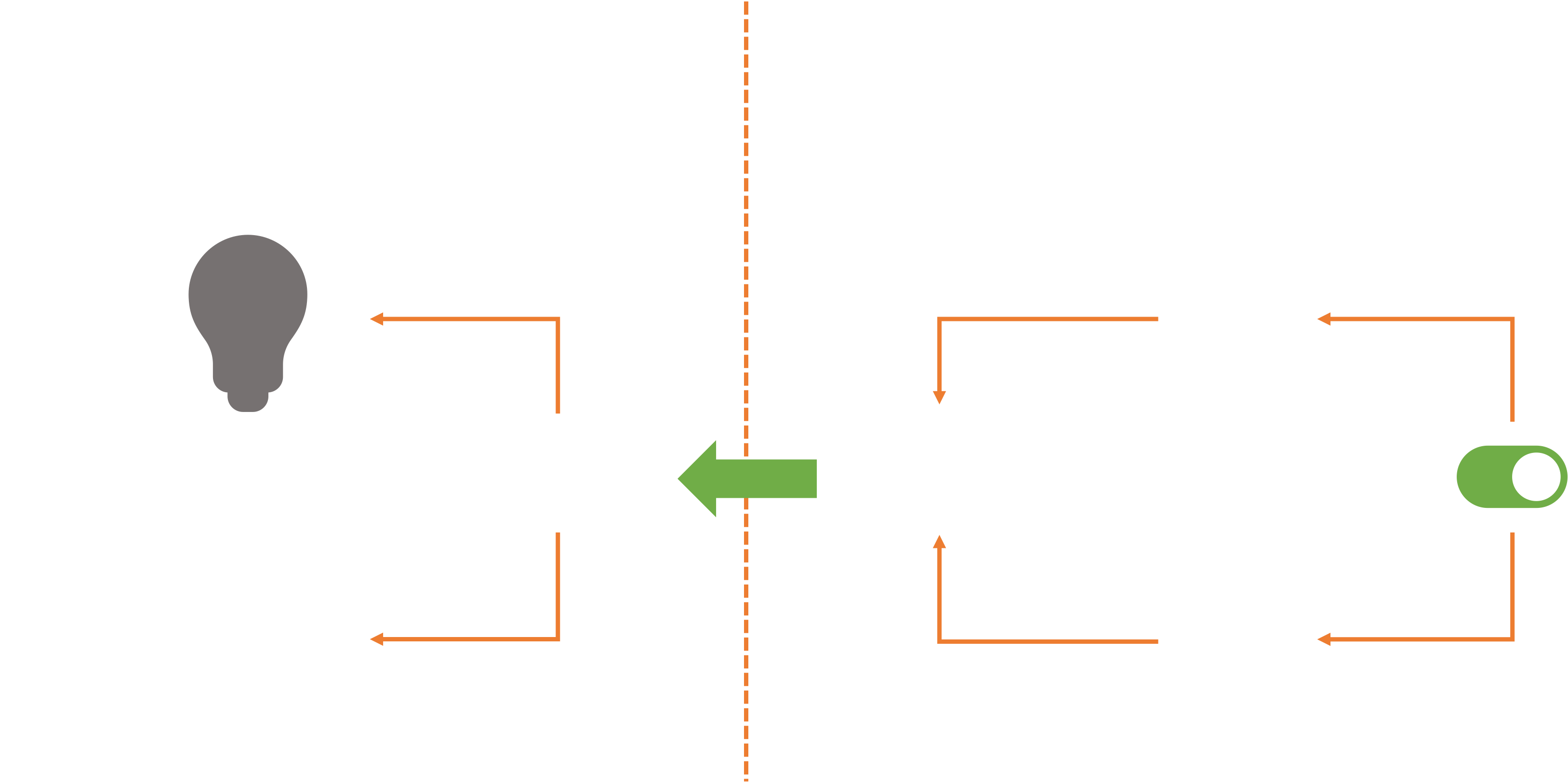

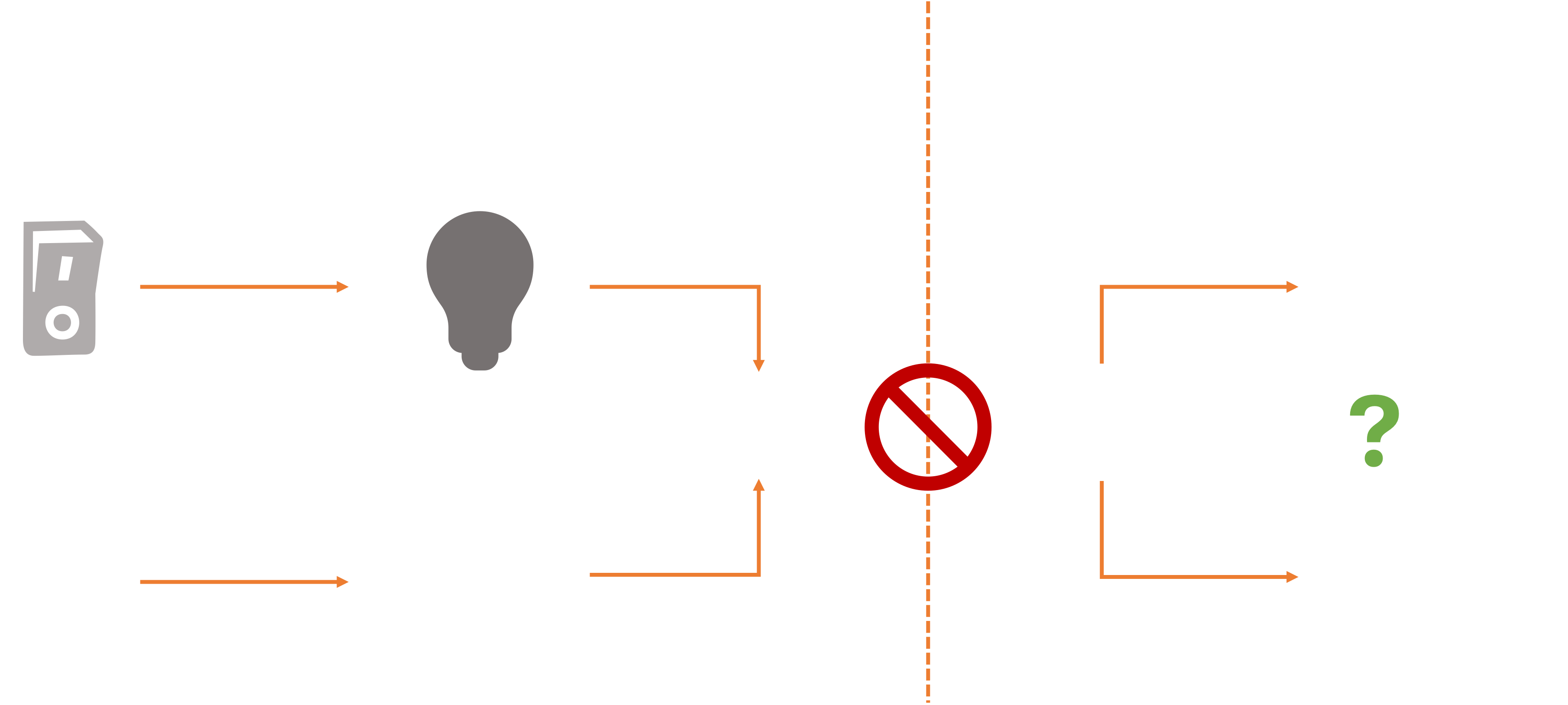

When we change the virtual state of the light (on the dashboard), the actual light bulb may change state, but the light switch itself doesn’t actually move.

For that to happen, we would need a remote assistant willing to make sure the state of the switch and the light bulb are in sync.

You might say the Digital World is a representation of the Light Bulb, not the Light Switch, and you would be correct.

But to the user, the state of the physical and digital worlds no longer matches. This is not good and can create doubt and confusion.

What’s more, what happens if the network connection goes out?

Now, we don’t really know if the Digital State is truly representative of the Physical world. Is the light bulb actually on, or did our remote command never reach the bulb?

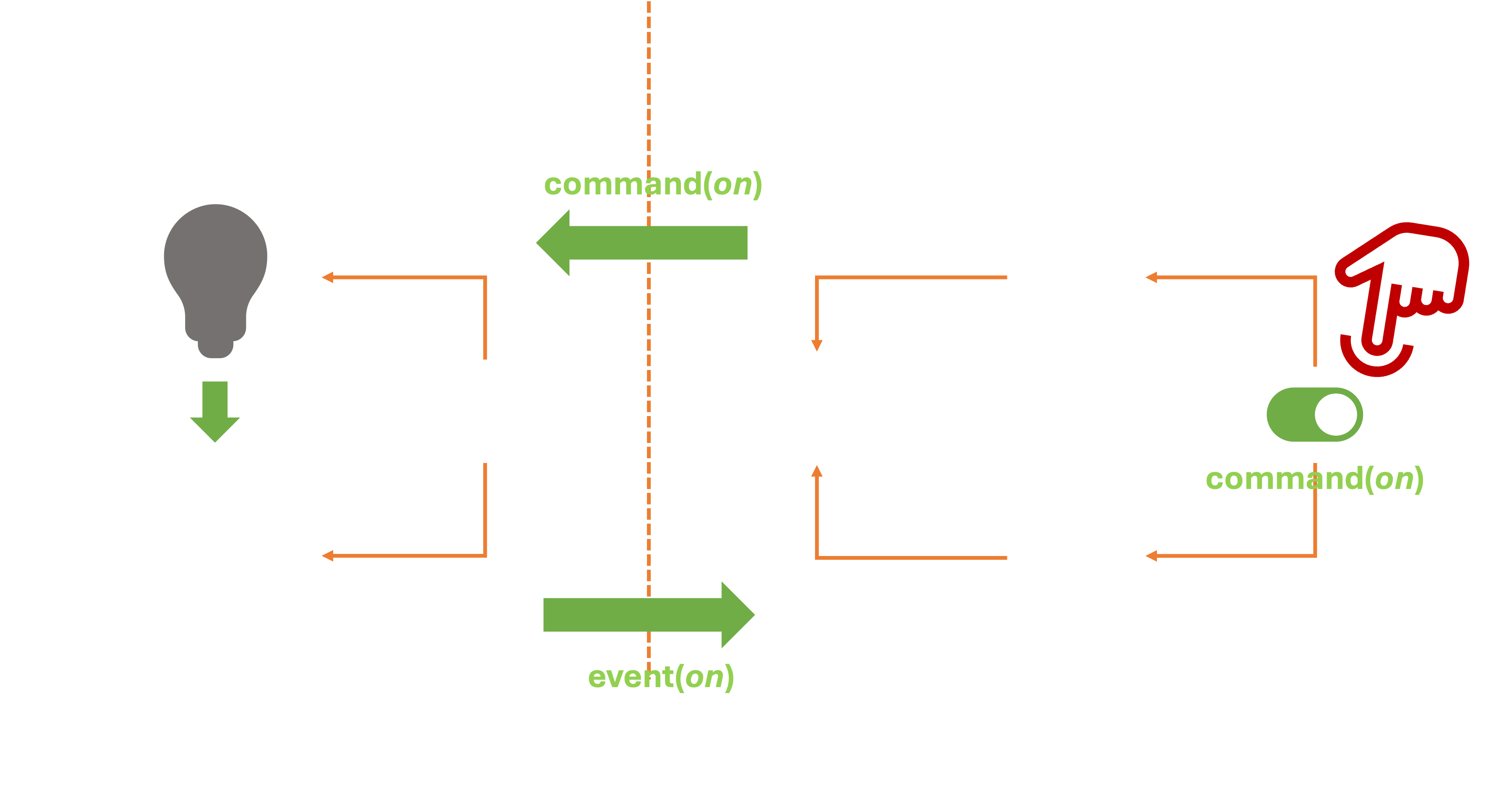

One way to make sure things are done is to split the events into commands and events. You send a turn on command from the Digital world, and it gets sent to the Physical world, where the light is turned on. This generates a state change event which then returns to the Digital world, confirming that it was actually done.

In a real system, a fallback timeout may be implemented in case a command’s confirmation is not received within a reasonable amount of time. The system can try sending it again, or it could generate an error and notify someone.

Heartbeat

Let’s take it one step further. What if the power has gone out at the switch/bulb location?

Now, we’ve got bigger problems.

Maybe we can turn it into a romantic, candle-lit evening with our light-switch assistant?

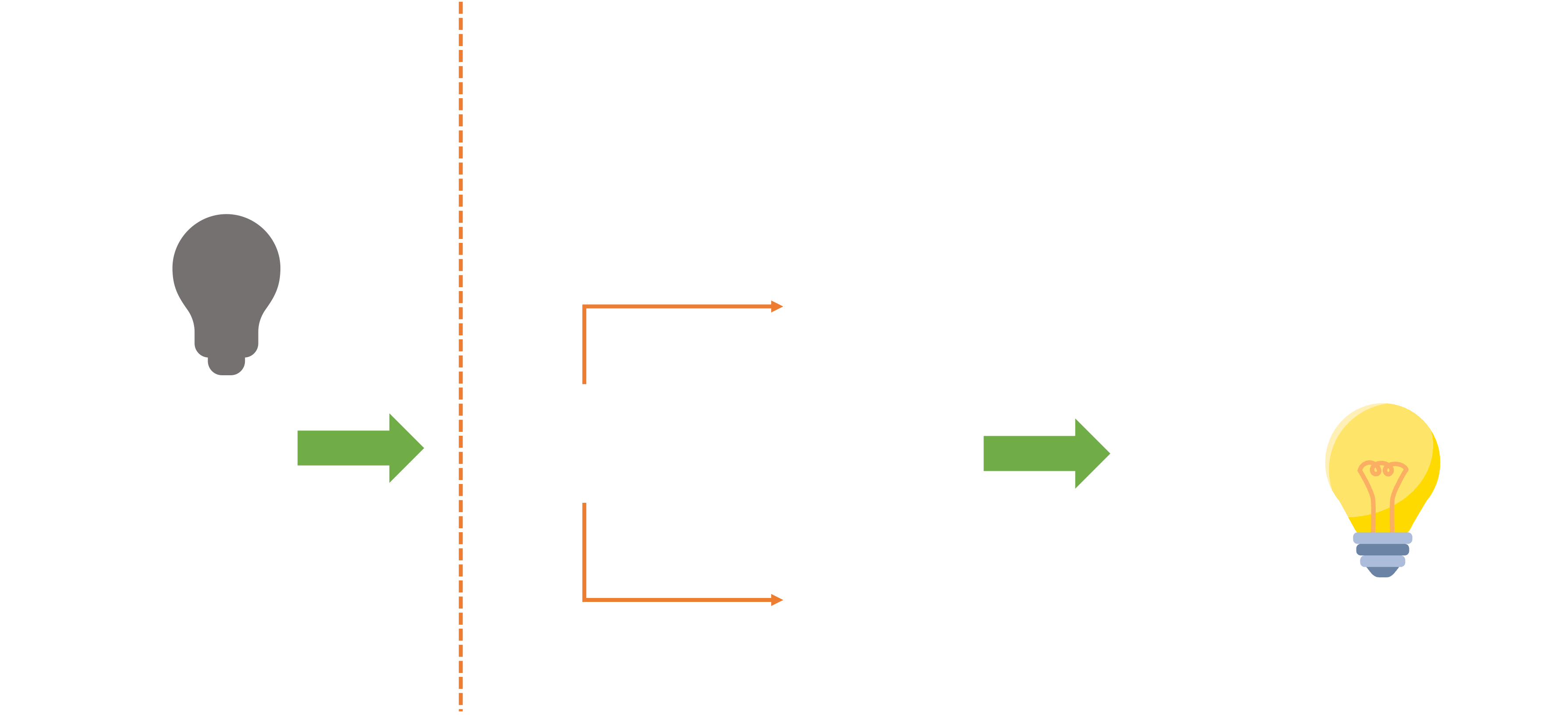

There is a way to at least determine when a failure occurs in communicating state changes between the Digital and Physical worlds. We call this Keep-Alive or Heartbeat.

This is where the Physical World periodically sends a signal to the Digital side, indicating all is well. If the signal fails to arrive on time, the Digital side can notify someone and mark the light state as unreliable.

Another approach is to have the Digital side initiate an Are You OK signal periodically, and if it doesn’t receive a response, it can signal a problem. In practice, we don’t want to generate too many false negatives so either side tries a few times before hitting the panic button.

Here’s the one thing to remember in all this:

The absence of a signal... is a signal.

We’ll come back to that later.

Now extrapolate from this simple example to a complex world of switches, sensors, actuators, and motors. A world of 3D models and Augmented and Virtual Reality scenes. Where values are not limited to on/off, but a range of values. Where changes in the Physical World (aka events) are logged, analyzed, and charted. And anomalies in the values can be studied to predict potential future failures.

In the industrial or Smart Home world, this is called a Digital Twin, and it’s a pretty big deal in the business world.

Personal Digital Twins

What the heck does this have to do with AI Companions or Privacy?

Funny you should ask, because we are now going to expand the definition and talk about a

Let’s start with a Privacy Digital Twin.

To recap, in the previous section on Privacy we talked about the variety of attributes that might be stored for an individual. Values like name, age, or phone number.

We talked about immutable or unchangeable attributes like place of birth or birthday. But also about data that can be modified either by us or by some other entity that has been given permission by us to read or modify the data.

The thing is, managing all this data and monitoring who gets access to it and what level of Privacy to apply is tedious and, well…

What we need is a smart, ever-vigilant mechanism that represents our preferences, tracks our attributes, and notifies us when a violation occurs. Sound familiar?

Something that can manage the lenses and facets we discussed before, and generally ensure our Privacy is preserved. What’s more, such a system could (and should) be run on a device under our own control, such as a Smart Home hub or a more advanced version.

Here are the goals for an ideal system. It should support:

- Discovery: Allow others to find out how to access our private information.

- Permission: An easy-to-use mechanism to control who can see what and for how long

- Correct or Delete: Offer easy ways to correct errors or rescind data we no longer want out there.

- Stay Local: Maintain data as close to yourself as possible. This means on the edge, under your own control, instead of out on some unknown cloud.

- Distribute: Try to avoid single-points-of-failure and concentrated data. Splitting it apart and federating the data is the safest way to reduce the blast radius of the inevitable leak.

- Anonymize: Do as much as you can to avoid enabling Personally Identifiable Identifiers. Reduce your footprint as much as possible.

- Sharing: data with family, caregivers, those we conduct business with, acquaintances, automated systems, healthcare and financial providers, legal and government entities. Anyone we may encounter in real life or online.

- PubSub: Most data is dynamic and changes over time. We want to allow others to subscribe so they can be notified when something they need to know changes. We should have systems that monitor, notify, and allow us to rescind that access.

- Monitored: Think of this as leak detection. If something gets out inadvertently, it’s good to be aware of it.

- Change: Don’t leave pots of information static. This is the easiest way for it to be monitored directly or through side channels. A system that periodically changes things (without requiring any action on your part) makes it more challenging for data collectors.

- KeepAlive: Remember, absence of a signal is a signal itself. The system should notify us (or a designated other) when something that was supposed to change hasn’t. Think of it as a privacy heartbeat.

This would be a system that acts as our privacy avatar, our personal agent, or some trusted entity that can act on our behalf so we aren’t bothered.

The Other Digital Twin

There’s another way to leverage Digital Twins to represent us, and that is to model our physical, mental, and emotional states. Let’s call this one a Personal Digital Twin.

These attributes could then be used to represent the current state of our physical characteristics, like our blood pressure, sleep state, or glucose level. Or our emotional state as detected by other types of sensors. Perhaps a combination of our blood pressure, body temperature, stress level, or tone of voice.

Just like the industrial digital twin, these would be representations of the physical world’s values.

This may sound far-fetched, but not so much.

MiniMed™ Mobile App See insulin pump data and glucose levels on your smart device.

CareLink™ Connect App Designed for care partners, remotely view the glucose levels and insulin pump information of a person with diabetes.

Please note that there is no remote control for the pump.

This is not because it is not technically possible. It’s actually really easy to implement. However, given the current state of digital security, it creates a world of risk, including potential for physical harm and legal liability.

Imagine a ransomware group holding your insulin pump hostage until you pay up. Or someone hacking the network service and assassinating people.

Sounds sci-fi, but we’re already there. It won’t happen until we shore up the foundations that have been ad hoc, cobbled together.

The point is, the concept of a Human Digital Twin is not only possible but also viable. The issue is how we can implement it in such a way that it benefits us as users.

One area where it can be of great benefit is ElderCare, especially when there is a shortage of caregivers. This is when sensors can be deployed to monitor whether someone has fallen, forgotten to eat, experienced a blood pressure spike, or become confused and wandered away from home.

On the cloud side, we can create services where selective caregivers are given permission to access that information and receive notifications when something goes out of range or an unusual event is detected.

The same predictive techniques developed to detect when an industrial device is failing can also be applied to human attributes.

Not just detection. Also prediction.

_Personal Digital Twins bring us that option.

Back to Basics

Digital Twins (under control of the individual) are a perfect application for an AI Companion.

To make such a system work, we need to have a solid foundation for Privacy, Reliability, and Trust. If you go back to our first section on Privacy, it is evident that the foundation does not exist today.

If we want to reap these benefits in the future, we need to start building today, brick by brick.

Title Photo by leoni fleming on Unsplash