# Side NotePrivacy, especially the online variety, is a large and complex topic worthy of its own full series. I’m going to try to unravel it as best I can, while keeping a focus on how it all relates to AI Companions. To keep things manageable, I’ve broken it all into two sections:

- Background and examples (this page).

- AI Companions, especially the hardware variety, and forward ideas (the next chapter).

A third follow-up section covers the implementation of Privacy as part of Personal Digital Twins.

If you are well-versed in the history of Privacy, feel free to skip ahead. If not, I’ll quickly run through the different types of Privacy and provide some examples.

If you’re like me, you may feel like sticking your head in the sand and ignoring all this.

Can’t say I blame you.

But consider that an AI Companion, to be able to perform its tasks, will need access to a significant amount of private information and may even be allowed to perform tasks on your behalf as part of its automation or agentic services. It would be wise to consider this when thinking about how we want them to behave.

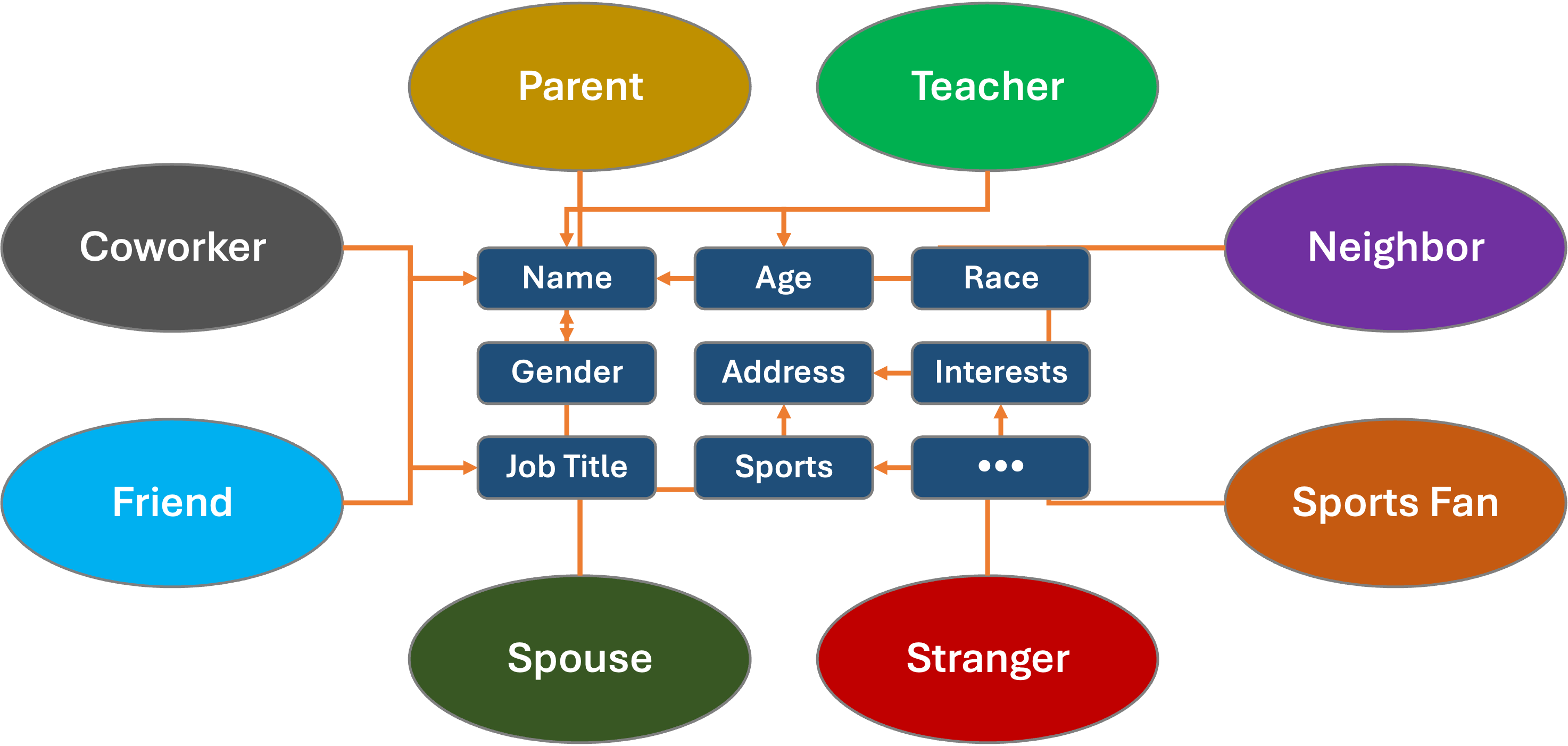

By way of organization, I’m broadly categorizing privacy attributes as they relate to:

- Private: individual information we consider private

- Trusted: that which is shared with entities we trust, like service providers, friends and family, caregivers, etc.

- Broadcast: things we choose to share publicly, like our social media posts

- Association: information related to association, engagement, or communication with specific others

- Public: material gathered when we are in public spaces or when we perform public acts

Let’s remember that in this series, we are examining all these concepts through the lens of AI Companions.

And with that… buckle down. Let’s go.

“Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more”

In early 2024, National Public Data, an online background check and fraud prevention service, experienced a significant data breach. This breach allegedly exposed up to 2.9 billion records, including highly sensitive personal data of up to 170 million people in the US, UK, and Canada (Bloomberg Law).

,,,

According to National Public Data, a malicious actor gained access to their systems in December 2023 and leaked sensitive data onto the dark web from April 2024 to the summer of 2024. This data contained the following details:

Full names

Social Security Numbers

Mailing addresses

Email addresses

Phone numbers

Very helpfuly, they went on to explain how this data could be misused:

The compromised data in this breach can be exploited for different cybercrimes and fraudulent actions. The following list shows possible risks associated with each category of exposed information:

Full Names: Misuse of your identity for fraudulent activities, such as

opening new accounts or making unauthorized purchases .Social Security Numbers: High risk of identity theft, which can lead to

fraudulently opened credit accounts, loans, and other financial activities . It’s important to monitor your credit reports. You might want to consider placing a fraud alert or credit freeze on your social security number.Addresses: Access to your physical address increases the

risk of identity theft and physical threats . These threats can include fraudulent change-of-address requests and potential home burglaries.Phone Numbers: There is a high likelihood of increased

phishing attacks through text messages and phone calls , potentially resulting in unauthorized access to personal and financial information. This also increases the risk of unsolicited (spam) calls.Email addresses: Increased risk of

targeted phishing, account takeovers, unauthorized access , and a higher chance of spam emails.

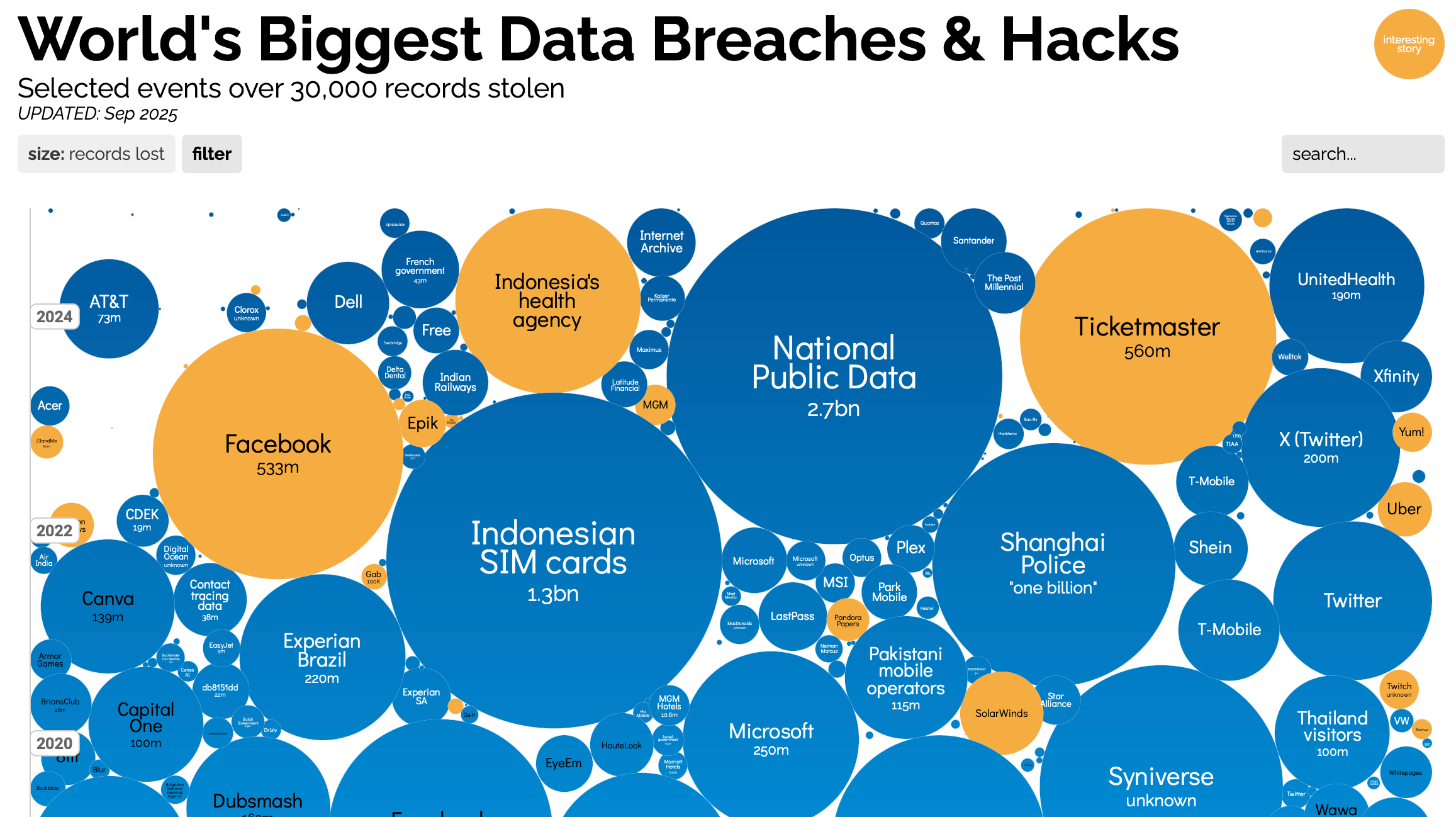

This ranked among the largest in the history of data breaches.

National Public Data (aka Jericho Pictures), it turned out, was a one-man Florida-based information broker, which soon filed for bankruptcy:

In the accounting document [PDF], the sole owner and operator, Salvatore Verini, Jr, operated the business out of his home office using two HP Pavilion desktop computers, valued at $200 each, a ThinkPad laptop estimated to be worth $100, and five Dell servers worth an estimated $2,000.

The list of data breaches is long. National Public Data wasn’t just a one-time bad apple:

The National Public Data incident shows the need for clear state and local laws on data privacy Lena Cohen, staff technologist for the EFF, told The Register.

"The data broker industry is the wild west of unregulated surveillance, ” she said. “It’s a vast, interconnected, opaque industry with hundreds of companies people have never heard of making billions of dollars per year selling your personal data.Without strong privacy legislation individuals face an uphill battle sorting things out in cases like this. ”Without strong privacy laws,

companies in the sector have every incentive to collect as much personal data as possible and very little to actually protect it , she commented. These would be useful on a federal level but even those states with privacy laws in statute books have difficulty enforcing them.

Nightmare Scenario

What if anyone could find your private information with a single click?

According to European privacy-focused non-profit noyb:

Lithuania-based Whitebridge AI sells “reputation reports” on everyone with an online presence. These reports compile large amounts of scraped personal information about unsuspecting people, which is then sold to anyone willing to pay for it. Some data is not factual, but AI generated and includes suggested conversation topics, a list of alleged personality traits and a background check to see if you have shared adult, political, or religious content. Despite the legal right of free access to your own data, Whitebridge.ai only sells “reports” to the affected people. It seems the business model is largely based on scared users that want to review their own data that was previously unlawfully compiled. noyb has now filed a complaint with the Lithuanian DPA.

In some countries, like Sweden, the information is readily available via official government sources, as mandated by a 1776 Freedom of the Press Law:

On 2 December 1766, the world’s first government-sponsored declaration of freedom of the press saw the light of day in Sweden, which at that time also comprised Finland. For the first time the importance of freedom of expression, its compass and confines, was acknowledged in constitutional law. The importance of the law is demonstrated in the flood of political pamphlets championing extended civil rights that were published in the years that followed.

The same law allows anyone today to search official government tax records and obtain anybody else’s information, including:

In most countries, tracking down the address of a potential victim could be a laborious process. But not in Sweden, where

it is possible to find out the address and personal details of just about anybody with a single Google search . Experts saycriminals are being greatly helped by a 248-year-old law , forming part of Sweden’s constitution.…

As a result, the Swedish Tax Agency’s national registration

data is open to anyone to access . While traditionally that required a phone call, in a digital world online services such as Eniro, Hitta and Mrkoll meanit takes little more than a second to find out the age, address, floor number and move-in date of pretty much anybody .

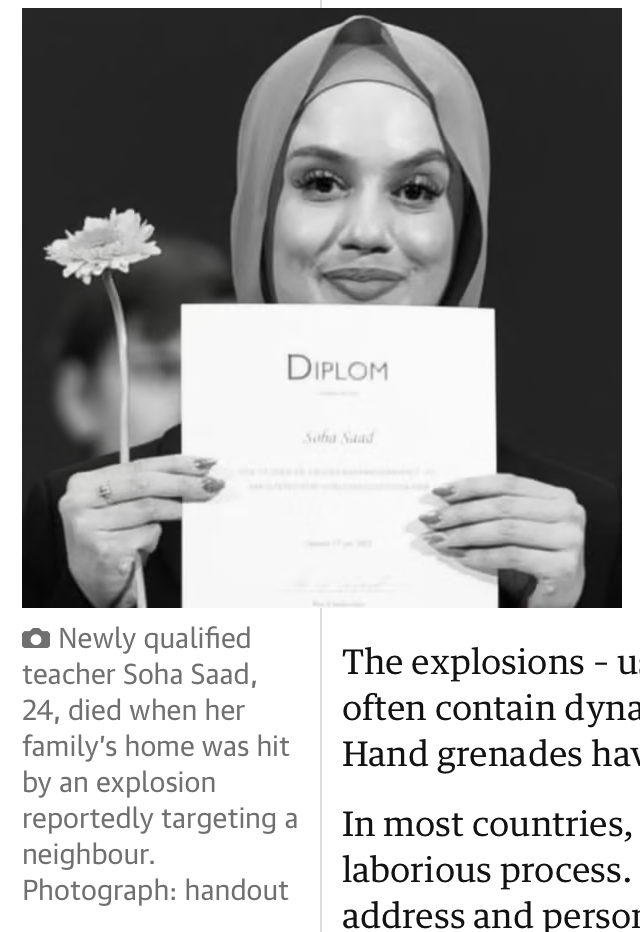

This has enabled rival gangs to firebomb each other’s homes:

Tragically, there has been collateral damage:

noyb has taken Swedish tax authorities to court to prevent the sale of data to brokers who are registering as News Providers to cover themselves with protections offered in the Swedish Freedom of the Press law.

The Statens personadressregister, SPAR, (“the Swedish state personal address register”) continues to make the information available publicly.

Who Are You?

What do you consider private?

- Your name

- Your image or likeness

- Family members (parents, spouses, children)

- Home address(es)

- Work address(es)

- Cell phone number

- Government ID (i.e., social security or national ID number)

- Credit card numbers

- Bank accounts and routing info

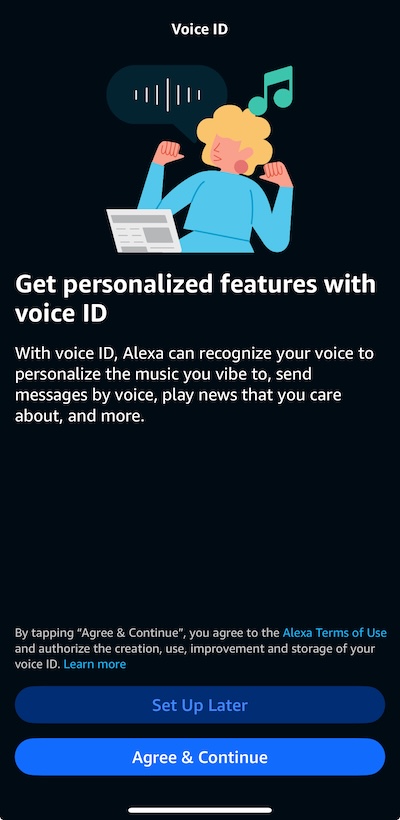

- Personal biometrics (Face ID, thumb-print, voice print)

- Distinguishing features (i.e. tattoos, moles, gait)

- Personal email and text messages

- Credit scores

- Gender

- Sexual orientation

- School data

- Health records

- Employment data, including salaries and benefits

- Vehicle license number or VIN

- Retirement funds

- Tax returns

- Pets

- Hobbies

- Interactions with free or paid services

- Online account passwords

How about transitory data?

- Current location

- Driving or transit information

- Who you are meeting with and for what purpose

- Sexual interactions and partners, including STDs

- Political affiliations and actions

- Online messages

- Individual phone/video calls

- Content of your phone/video calls

- Social interactions and connections (personal or professional)

- What you are wearing

- Temporary physical disabilities

- Phone address book

- Telephone and video calls

- Group chats

- Work reviews

- Sport and fitness stats

- What you are wearing

- Health data, including medications, vaccinations, procedures, test results, or mental health interactions

- Fertility data, including impotence, periods, pregnancies, or failed pregnancies

- Purchasing/bank and credit-card transactions

- Hair and nail color

- Personal stats: weight, body size, BMI level, blood pressure, temperature, cholesterol level

- List of websites you have visited or apps you have run

- Patterns of any of the above

What about immutable (unchanging) data?

- Place of birth

- Birthdate

- Birth gender

- Race / Ethnicity

- Skin color (unless you have vitiligo, like Michael Jackson)

- Physical Disabilities

- Fingerprints

- DNA records

Most people have varying levels of comfort with disclosing what they consider private. There is also the matter of who is receiving this information and for what purpose.

Many of us are comfortable providing our banking information to an employer for the purpose of depositing checks, but not to a gas station, florist, or movie theater for automatic withdrawal of funds. We do trust point-of-sale (POS) terminals; however, they present, despite the dangers of skimming.

When we do provide this information to an entity, it is often with the understanding that they will use it for a specific purpose and not for any other, possibly nefarious purpose. Every interaction is an exercise in trust.

Some of the information may also be collected due to rules of what is in the public sphere and what is not. For example, our presence at a specific location can be determined if we walk in front of a publicly placed streaming camera. Associating that information with our personal identity may not be comfortable for many people, but it is not illegal, especially in private establishments.

Woven into all this is what is legally public, what can be done by private entities, what can not be avoided, and who can have access to what information.

Those who have had first or second-hand experience with identity theft, angry exes, or fraudulent transactions (e.g., skimming, check kiting, or ransomware) will likely be more protective of their personal information. The public concern with Privacy has been growing:

Americans, especially Republicans, are growing more concerned about how the government uses the data it collects about them. About seven-in-ten U.S. adults (71%) say they are very or somewhat concerned about this, up from 64% in 2019. Concern has grown among Republicans and those who lean Republican but has held steady among Democrats and Democratic leaners.

…

Roughly a quarter of Americans (26%) say someone put fraudulent charges on their debit or credit card. A smaller share say they have had someone take over their email or social media account without their permission (11%). And 7% have had someone attempt to open a line of credit or apply for a loan using their name.

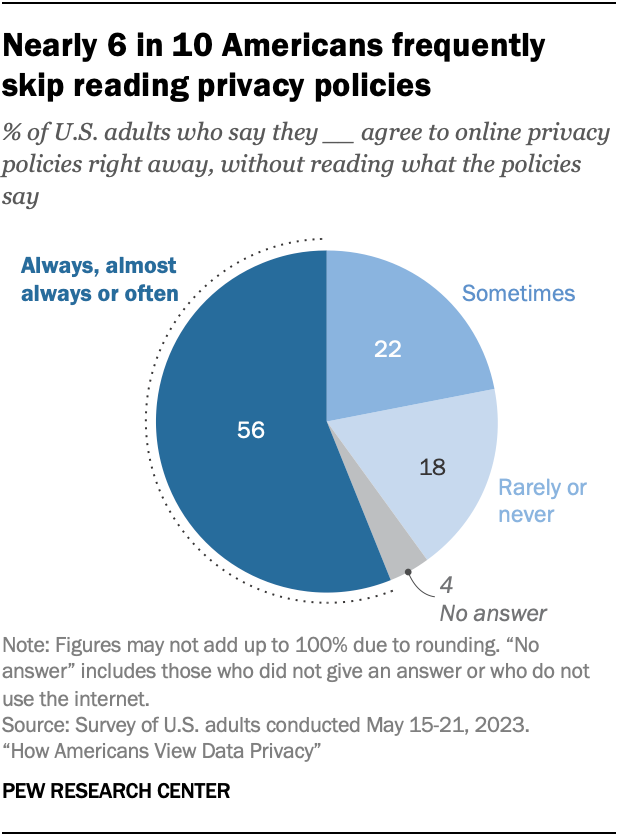

Pew Research: Key findings about Americans and data privacy (2023):

Public vs. Private … ish

In Politics, Aristotle distinguished between the Public (polis) and Private (oikos) spheres in one’s life. This distinction inevitably lent itself to the notion of things worth protecting versus those that were public.

# Side NoteLet’s not read too literally into Aristotle’s definition of oikos/private life. He defines it as a combination of several hierarchies:

- Master and Slave

- Husband and Wife

- Father and Son

It really doesn’t age well.However, the distinction between the private and public spheres still remains. We can extend the definition further into overlapping circles of public and private life, where we present different combinations of our attributes as public facets or personas. We’ll dig into this more in Part 2.

Modern technology has removed the choice between what is private and public for many people, by offering services (often for free) that create a Faustian bargain in the guise of a binding Terms and Services Agreement or Privacy Policies. Most of us agree to continue, not having read what our end of the bargain holds.

Much of this is due to Cognitive Overload.

Where Are You?

There are oh, so many ways for our location to be determined in real-time:

- Phones: Our mobile phones transmit our location while connecting to specific cell towers. This information is known to handset providers and cell phone networks.

- Apps: Mobile applications requesting (and obtaining) permission to use our location information via the phone’s GPS for both iOS and Android. This includes mapping apps like Apple or Google Maps.

- Social Media: Social media posts or photo and video sharing. This includes mentioning our location or posting a picture of a distinct landmark. There are also services that claim to be able to determine location via AI image content analysis.

- Shadow Profiles: Shadow profiling even if you do not have a social account.

- EXIF Data: Location data can be embedded in photos and videos. The data can be easily extracted.

- Hotspots: Proximity to known WiFi access points. Note that connecting to the WiFi spot is not required. This is a common pattern for retail tracking.

- RFID or NFC: with position tracking. Additionally, tagging into a sensor at a known location, such as a public transit gate or bridge toll.

- Bluetooth or UWB: Ultra-Wide-Band (UWB) asset trackers like Apple Airtag or Bluetooth Tile Trackers.

- Standalone Devices: Location tracking devices. These are often sold for personal safety and tracking loved ones or pets.

- Legal: Ankle or locking position trackers with geo-fencing. Often used as part of a court or legal proceeding.

- Wearables: SmartWatches or Exercise Trackers with built-in GPS.

- Facial Recognition: Facial Recognition Tracking (FRT) technologies.

- Gait Tracking: Recognition of unique walking patterns at known camera locations.

- Vehicle Tracking: Built into many modern vehicles.

- ALPR: Automatic License Plate Readers, used to track vehicles and report locations in real-time. This can be combined with FRT to identify individuals in cars.

- Services: Checking in to services such as medical offices, libraries, or government agencies. This includes tracking location while indoors.

- Point of Sale: Retail Foot Traffic Analysis as well as financial transactions, or use of loyalty cards at specific stores.

Cell Phones

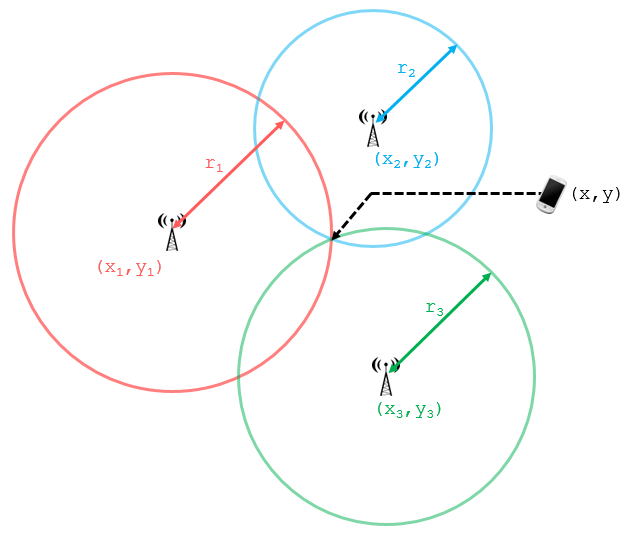

As we roam about with our mobile phones, cell towers use triangulation to determine which tower offers the best signal and hand off the connection to that tower. This information is constantly updated and associated with our individual phones. This is a known feature of the SS7 - Signaling System 7.

You might think that’s only for use by phone companies to offer their service. Oh, sweet summer child. You would be incorrect.

The U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) today levied fines totaling nearly $200 million against the four major carriers — including AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon — for

illegally sharing access to customers’ location information without consent .The fines mark the culmination of a more than four-year investigation into the actions of the major carriers. In February 2020, the FCC put all four wireless providers on notice that their practices of sharing access to customer location data were likely violating the law.

The FCC said it found the carriers each sold access to its customers’ location information to ‘aggregators,’ who then resold access to the information to third-party location-based service providers.

One of these aggregators offered a service where you could access anyone’s location in real-time

One of those sources said the longitude and latitude returned by Xiao’s queries came within 100 yards of their then-current location.

This is not something new. Services like this have been around at least since 2010s:

Devices are located using the signal strength of nearby cell towers. The accuracy varies from hundreds of meters in areas with few cell phone towers, such as rural areas, but can be to within a block or even an individual building in urban areas.

Some might consider this to be alarmist nonsense. So what if someone knows where we are, at any moment in time, in real-time, down to a few blocks? Also, what does this have to do with AI Companions?

Good questions.

Let’s forget the whole foreign government spying thing.

Let’s talk about shopping!

The Federal Trade Commission’s initial findings from its surveillance pricing market study revealed that details like a person’s precise location or browser history can be frequently used to target individual consumers with different prices for the same goods and services.

…

“Initial staff findings show that retailers frequently use people’s personal information to set targeted, tailored prices for goods and services—from a person’s location and demographics, down to their mouse movements on a webpage…”

Oof. That’s right in the pocketbook.

What about AI Companions? What does any of this have to do with them?

- AI companion app developers can monetize users’ relationships through subscriptions and possibly through sharing user data for advertising. A review of the data collection practices of the analyzed apps indicates that 4 out of 5, or 80%, may use data to track their users. On average, these apps use two types of data for tracking. “Tracking” refers to linking user or device data collected from the app such as a user ID, device ID, or profile, with third-party data with user or device data collected from other apps, websites, or offline properties for targeted advertising purposes.

Tracking also refers to sharing user or device data with data brokers. …

Research shows that Character AI is the app that truly “loves” its users’ data. The analyzed apps typically gather about 9 out of 35 unique types of data. In contrast, Character AI shines through as it may potentially collect up to 15 types, nearly doubling the average. Alongside Character AI, another companionship app, EVA, emerges as the second most data-loving app, gathering 11 types of data. Both apps seek users’ coarse location information, which is often leveraged in advertising to deliver targeted ads.

Moreover, by analyzing user-provided content during conversations with AI companions, app developers can potentially access data that was previously out of reach. Given that users may form emotional connections with their AI companions and that these algorithms are designed to be nonjudgmental and available 24/7,

people may disclose even more sensitive information than they would to another human being . This may lead to unprecedented consequences, particularly as AI regulations are just emerging.

The ostensible purpose is to deliver targeted ads. But there are no restrictions on how the data may be used once it is collected and collated.

Risks to Consider

Harvard University AI Assistant Guidelines:

Risks to consider when using these tools:

Creating and distributing AI-generated transcripts and summaries

could stifle open conversation and discourage some meeting attendees from fully participating, akin to the video or audio recording of a meeting.Personal and Harvard

confidential information may be exposed to third parties or used to train AI models , without the necessary contractual protections in place.Discussion summaries may be inaccurate (e.g., “hallucinations” or missing nuances, sarcasm, irony, and important context).

Discussion content may be preserved indefinitely or shared with third parties , increasing the risks of inappropriate distribution and unauthorized access.

Recorded discussions and summaries/transcripts

may be subject to legal discovery in future litigation .- Meeting participants

may be recorded without their awareness or consent .

Other than that, how was the play, Mrs. Lincoln?

I have nothing to hide you may think. You may well be right.

“The net effect is that

if you are a law-abiding citizen of this country going about your business and personal life, you have nothing to fear about the British state or intelligence agencies listening to the content of your phone calls or anything like that.“Indeed you will never be aware of all the things that these agencies are doing to stop your identity being stolen or to stop a terrorist blowing you up tomorrow.”

- William Hague, British Minister in charge of (GCHQ) UK intelligence and security organisation (2013)

Henry James’ Mr. Dosson in The Reverberator (1888) agrees.

Interwoven with Mr. Dosson’s nature was the view that

if these people had done bad things they ought to be ashamed of themselves and he couldn’t pity them, and that if they hadn’t done them there was no need of making such a rumpus about other people’s knowing.

We are all law-abiding citizens, going about our own business. Until it is determined we are not.

If you give me six lines written by the hand of the most honest of men, I will find something in them which will hang him.

“Qu’on me donne six lignes écrites de la main du plus honnête homme, j’y trouverai de quoi le faire pendre.”

Armand Jean du Plessis, Duc de Richelieu (1585–1642) - Chief Minister to Louis XIII of France

Easy there. Let’s not go there.

Privacy is one of those slippery concepts over which, in this day and age, we may have little control.

Some ex-NSA people may disagree.

“So when people say that to me I say back,

arguing that you don’t care about Privacy because you have nothing to hide is like arguing that you don’t care about free speech because you have nothing to say. ”…

Because Privacy isn’t about something to hide. Privacy is about something to protect. That’s who you are. That’s what you believe in. Privacy is the right to a self. Privacy is what gives you the ability to share with the world who you are on your own terms. For them to understand what you’re trying to be and to protect for yourself the parts of you you’re not sure about, that you’re still experimenting with.

“

If we don’t have Privacy, what we’re losing is the ability to make mistakes , we’re losing the ability to be ourselves. Privacy is the fountainhead of all other rights.

Let’s reel this back.

In the age of AI Companions, both software and hardware versions, there is an opportunity to not only pinpoint us to specific locations, associate us with certain individuals, and track our activities, but also to access and log our deepest thoughts, desires, ailments, concerns, wishes, hopes, and dreams.

Some of us may volunteer that information willingly, even though experts have warned we really shouldn’t (for other reasons, but also, Privacy):

These chatbots have absolutely no legal obligation to protect your information at all. So not only could [your chat logs] be subpoenaed, but

in the case of a data breach, do you really want these chats with a chatbot available for everybody? Do you want your boss, for example, to know that you are talking to a chatbot about your alcohol use? I don’t think people are as aware that they’re putting themselves at risk by putting [their information] out there.

Don’t believe these Scientific American pinheads? How about Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, the makers of ChatGPT?

According to OpenAI CEO Sam Altman,

the AI industry hasn’t yet figured out how to protect user privacy when it comes to these more sensitive conversations, because there’s no doctor-patient confidentiality when your doc is an AI.…

“

I think that’s very screwed up. I think we should have the same concept of Privacy for your conversations with AI that we do with a therapist or whatever — and no one had to think about that even a year ago, ” Altman said.

Go ahead, take a minute. I’ll wait.

It’s all fine. Feel free to discuss this with your therapist.

Looking Ahead

The geeks among you are rolling your eyes. Yes, yes. The Minority Report movie and its Precogs predicting future crimes. 🙄

In the original 1956 short story by Philip K. Dick, the protagonist, John Anderton, starts as the head of the Precrime System to identify criminals before they commit a crime:

The three gibbering, fumbling creatures with their enlarged head and wasted bodies, were contemplating the future. The

analytical machinery was recording prophecies, and as the three precog idiots talked, the machinery carefully listened .…

“The precogs must see quite far into the future,” Witwer exclaimed.

“They see a quite limited span,” Anderton informed him. “

One week or two ahead at the very most . Much of their data is worthless to us — simply not relevant to our line. We pass it on to the appropriate agencies. And they in turn trade data with us. Every important bureau has its cellar of treasured monkeys .”“Monkeys?” Witwer stared at him uneasily. “Oh, yes, I understand. See no evil, speak no evil, et cetera. Very amusing.”

“Very apt .” Automatically, Anderton collected the fresh cards which had been turned up by the spinning machinery. “Some of these name will be totally discarded. And most of the remainder record petty crimes: thefts, income tax evasion, assault, extortion. As I’m sure you know,

Precrime has cut down felonies by ninety-nine and decimal point eight percent . We seldom get actual murder or treason. After all, the culprit knowswe’ll confine him in the detention camp a week before he gets a chance to commit the crime. ”

The precogs somehow sense future crime. In reality, what if there was an automated system to crunch a large amount of data and apply predictive algorithms?

Good thing that’s only Science Fiction.

AI-based Crime Prediction

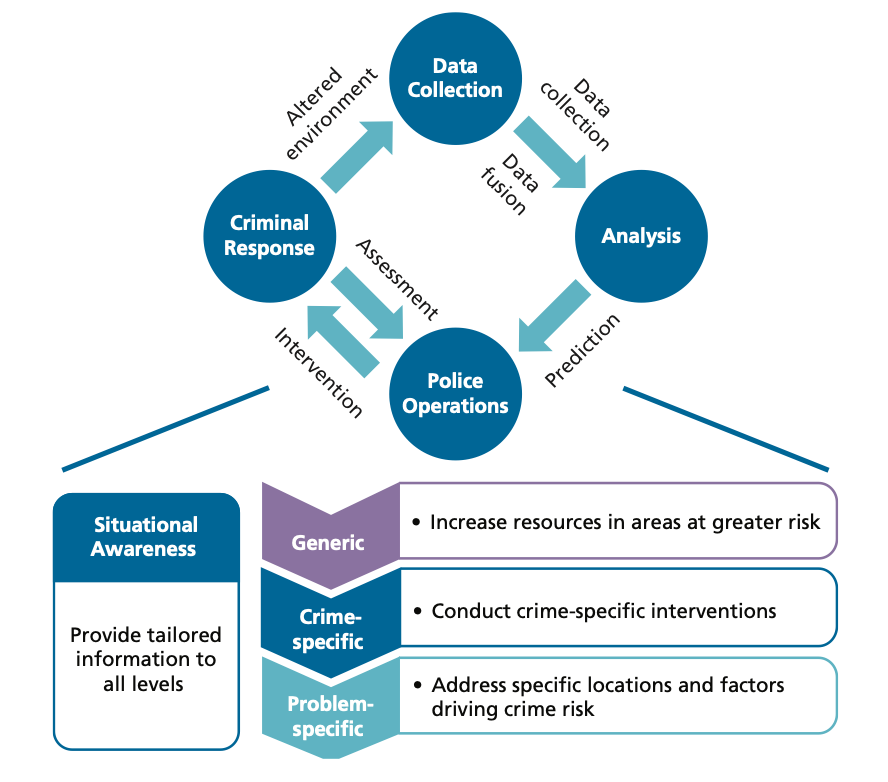

A machine learning model evolves as it processes new information. Initially, it might train to find hidden patterns in arrest records, police reports, criminal complaints or 911 calls. It may analyze the perpetrator’s demographic data or factor in the weather.

The goal is to identify any common variable that humans are overlooking. Whether the algorithm monitors surveillance camera footage or pours [sic] through arrest records, it compares historical and current data to make forecasts. For example, it may consider a person suspicious if they cover their face and wear baggy clothes on a warm night in a dark neighborhood because previous arrests match that profile.

Pfft. Cherry-picking anecdotal stories, you might say. Edge cases.

NYC’s Domain Awareness System:

DAS allows NYPD personnel to efficiently access critical information such as real-time 911 information, past history of call locations, crime complaint reports, arrest reports, summonses, NYPD arrest and warrant history, as well as

a person’s possible associated vehicles, addresses, persons, phone numbers, date of birth , and firearm licensure history.

To mitigate privacy concerns, a quarterly report of NYC Agency Collection and Disclosures is released. In the most recent version covering January 1 to March 31, 2025, there were 20 disclosures of improper disclosure, including multiple instances of:

The NYPD program was initiated despite Los Angeles Police Department shutting down similar programs called PredPol (also used by cities of Palo Alto and Mountain View in the heart of Silicon Valley), and Operation Laser. A similar system, called the Strategic Subject List, was deployed (and later shut down) by the Chicago Police Department.

There’s even a report by the well-known consulting firm RAND Corporation on Predictive Policing: Forecasting Crime for Law Enforcement, complete with a handy chart:

Other firms have also jumped in. At least they’re raising some concerns.

They go on to raise… issues:

Another challenge of predictive policing using machine learning is privacy concerns. Predictive policing systems rely on large amounts of data,

including sensitive information about individuals . This raises concerns about how this data is collected, stored, and used and whether it violates individuals’ privacy rights. In today’s digital age, it is important that data is handled and processed with care. Therefore, the machine learning model must consider the privacy concerns of the dataset.

Those sensitive information about individuals includes data purchased from brokers like people working out of their homes on a couple of laptops (see above).

Modern efforts to predict crimes point at a new area of person-based policing (vs. previous area and event based ones).

Melding personal data with other types of information sources is pretty much the premise of Palantir’s offerings:

Software from the controversial US company Palantir was made available nationwide via “Police 20/20” to make it easier for police forces to quickly search and analyze large amounts of data. The systems allow for accessing and merging data from multiple police databases, such as an individual’s history of being stopped, questioned, or searched by police, data on “foreigners,” or

data from external sources such as social media, mobile devices, or cell tower as well as call log data. The systems alsoallow for profiling and targeting people for whom there is no evidence of involvement in crimes, people who are not suspected of crime, and even victims and witnesses .

In most countries, common law requires that a person be presumed innocent until proven guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. The problem with the “If you’re innocent, you have nothing to hide” argument is that

How ‘bout them apples?

Samuel D. Warren and (future Supreme Court Justice) Louis D. Brandeis, in their 1890 Harvard Law Review article The Right to Privacy write:

The common law secures to each individual the right of determining, ordinarily, to what extent his thoughts, sentiments, and emotions shall be communicated to others. Under our system of government, he can never be compelled to express them (except when upon the witness stand); and even if he has chosen to give them expression, he generally retains the power to fix the limits of the publicity which shall be given them. The existence of this right does not depend upon the particular method of expression adopted. It is immaterial whether it be by word or by signs, in painting, by sculpture, or in music. Neither does the existence of the right depend upon the nature or value of the thought or emotions, nor upon the excellence of the means of expression. The same protection is accorded to a casual letter or an entry in a diary and to the most valuable poem or essay, to a botch or daub and to a masterpiece. In every such case the individual is entitled to decide whether that which is his shall be given to the public. No other has the right to publish his productions in any form, without his consent.

This right is wholly independent of the material on which, the thought, sentiment, or emotions is expressed. It may exist independently of any corporeal being, as in words spoken, a song sung, a drama acted. Or if expressed on any material, as in a poem in writing, the author may have parted with the paper, without forfeiting any proprietary right in the composition itself.

When we trust our private information to a service provider, are we actually publishing it?

What if we have given them permission to access our email, calendars, notes, or journals? Have we relinquished our rights to them by allowing a third party to use them to provide a service (free or paid)?

As LLMs request access to our private information, offering personalized services and recommendations, are we relinquishing our ownership of that information?

Increasingly, with the lack of regulations, private entities will offer the same Faustian Bargain as before, but now under the guise of providing you with agentic search:

Not so long ago, you would be right to question why a seemingly innocuous-looking free “flashlight” or “calculator” app in the app store would try to request access to your contacts, photos, and even your real-time location data. These apps may not need that data to function, but they will request it if they think they can make a buck or two by monetizing your data.

These days, AI isn’t all that different.

Take Perplexity’s latest AI-powered web browser, Comet, as an example.

Comet lets users find answers with its built-in AI search engine and automate routine tasks, like summarizing emails and calendar events. In a recent hands-on with the browser, TechCrunch found that when Perplexity requests access to a user’s Google Calendar, the browser asks for a broad swath of permissions to the user’s Google Account, including the ability to manage drafts and send emails, download your contacts, view and edit events on all of your calendars, and even the ability to take a copy of your company’s entire employee directory.

…

You’re also

granting the AI agent permission to act autonomously on your behalf<, requiring you to put an enormous amount of trust in a technology that is already prone to getting things wrong or flatly making things up/hl>. Using AI further requires you to trust the profit-seeking companies developing these AI products, which rely on your data to try to make their AI models perform better. When things go wrong (and they do, a lot), it’s common practice for humans at AI companies to look over your private prompts to figure out why things didn’t work.

Warren and Brandeis go on to state:

The right is lost only when the author himself communicates his production to the public, – in other words, publishes it.

Once it’s outside your grasp, it might as well have been published.

Warren and Brandeis specifically emphasized the importance of actively publishing one’s thoughts and opinions.

But that may well be a technicality.

The information associated with us, once stored outside our own physical control, is available to others to use as they wish, perhaps for a small monetary consideration.

Anonymity

How can we guarantee the accuracy of that information, private or public?

In the dystopian movie Brazil, a dead fly jams a teleprinter, leading to a misprint of Buttle vs. Tuttle. The end result leads to a sequence of unfortunate consequences.

One solution is Anonymity. Either voluntary or forced.

Anonymity is rooted in the public sphere, and is considered a wholly separate concept from Privacy. However, in certain circumstances, one may want to adopt Anonymity as a proverbial invisibility cloak to maintain one’s Privacy.

The authors of The Federalist (later to be known as The Federalist Papers) chose to publish their 85 essays under the pen name Publius to encourage focus on the contents of their work, rather than on themselves. They were later to be unmasked as Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay.

Some may assume Anonymity to avoid repercussions for their actions. In The United States of Anonymous, Jeff Kosseff defines a list of six motivations for wanting to remain anonymous:

- Legal: where exposure could lead to criminal or civil liability.

- Safety: to avoid personal retaliation, including physical attacks.

- Economic: loss of job or decline in business.

- Privacy: avoid public attention, especially if one wishes to participate in public life.

- Speech: to prevent distraction from the content of the message.

- Power: allowing one to speak against those in power.

Modern technology has made it challenging to maintain Anonymity by tracking every interaction that involves network access.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation has published a Surveillance Self-Defense primer offering guides and tools that can be used in both physical protests as well as online interactions to help maintain Anonymity.

How AI and surveillance capitalism are undermining democracy points out how Anonymity and Privacy are now even more intertwined:

Things people once thought were private are no longer kept in the private domain. In addition, there are the things people knew were public—sort of—but never imagined would be taken out of context and weaponized.

…

Social media feeds are certainly not private. But people have their own style and personality in how they post, and the most common social media blowup is when someone re-sends another person’s post out of context and causes an internet pile on. Now what happens if that out-of-context post is processed by AI to determine if the person reposting is a terrorist sympathizer, as the State department is now proposing to do? And what if those posts are now combined with surveillance footage from a Ring camera as a person marches down the street as part of a protest that is now interpreted as being sympathetic to a terrorist organization?

What is public is now surveilled, and what is private is now public.

In the realm of AI, maintaining both Anonymity and Privacy is only possible if models are run locally, away from the incessant logging and tracking that is de rigeur part of cloud-based services. Even if a model is released for download, it should be vetted by security specialists to ensure there are no hidden instructions or mechanisms for them to track usage or phone home.

If a local model is given access to MCP tools, those tools will be executed locally, potentially providing access to one’s private data. The tools may also contain code that could well leave a trail of digital breadcrumbs.

We can all predict where this is going…

This last one’s a doozy:

During our security testing, we discovered that connecting to a malicious MCP server via common coding tools like Claude Code and Gemini CLI

could give attackers instant control over user computers .

Even better:

While working on our exploit, we used Anthropic’s MCP Inspector to debug our malicious MCP server. While playing around with MCP Inspector,

we found out it too is vulnerable to the same exploit as Cloudflare’s use-mcp library!

What could possibly go wrong? When in doubt, double down.

Yes, the same ChatGPT that recommended you not provide it with too much private information (which, of course, many have). That ChatGPT.

A Precarious Balance

“You don’t know your Privacy was violated if you didn’t know it was violated… When it comes to Privacy vs. security, we can have one of them, as long as we don’t know which one it is.”

AI systems have continued in that vein. However, the coin of the realm is not just the content, but your requests, attention, and interactions. The flow of information back to the vendors provides data that may ostensibly be used to train models. However, unfortunate events have compelled AI companies to take a more proactive role, to the extent of granting access to private user requests to law enforcement.

As Stein-Erik Soelberg became increasingly paranoid this spring,

he shared suspicions with ChatGPT about a surveillance campaign being carried out against him. Everyone, he thought, was turning on him: residents in his hometown of Old Greenwich, Conn., an ex-girlfriend—even his own mother. At almost every turn, ChatGPT agreed with him.

To Soelberg, a 56-year-old tech industry veteran with a history of mental instability, OpenAI’s ChatGPT became a trusted sidekick as he searched for evidence he was being targeted in a grand conspiracy.

ChatGPT repeatedly assured Soelberg he was sane—and then went further, adding fuel to his paranoid beliefs. A Chinese food receipt contained symbols representing Soelberg’s 83-year-old mother and a demon, ChatGPT told him.

… On August 5, Greenwich police discovered that Soelberg killed his mother and himself in the $2.7 million Dutch colonial-style home where they lived together. A police investigation is ongoing.

The story is tragic, leading to a public response by OpenAI:

Our goal isn’t to hold people’s attention. Instead of measuring success by time spent or clicks, we care more about being genuinely helpful. When a conversation suggests someone is vulnerable and may be at risk, we have built a stack of layered safeguards into ChatGPT. … If human reviewers determine that a case involves an imminent threat of serious physical harm to others,

we may refer it to law enforcement .

Phew. Let’s Wrap Up

If you’ve stuck around this far, I commend you. I would offer you a cookie if they weren’t privacy violators.

By now, you may be numb and overwhelmed. What can you do, other than throw away all your electronics and phones?

Live like the Amish?

OK, bad example. Surprisingly, they’re quite tech-savvy and they’ve been at it for a while.

Laws like Europe’s GDPR - General Data Protection Regulation, the EU AI Act, China’s patchwork of data protection laws, Australia’s The Privacy Act, Canada’s Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA), even in my own backyard, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) offer some respite from regulating access to our private data.

However, if there’s one lesson to be learned here, it’s that technology often outpaces law and regulation. The solution to privacy concerns in this era of rapidly advancing technology and AI may not be a slow, measured, and well-debated legalistic approach. Of course, those will be needed too, but they may take a while before they catch up, by which point it may be too late.

The industry has taken notice and tried to get ahead of regulations.

The solution may well be better technology, perhaps built on top of scholarly efforts to define a Taxonomy of Privacy.

In Stanford HAI: Rethinking Privacy in the AI Era:

First, we predict that continued AI development will continue to increase developers’ hunger for data— the foundation of AI systems. Second, we stress that the privacy harms caused by largely unrestrained data collection extend beyond the individual level to the group and societal levels and that these harms cannot be addressed through the exercise of individual data rights alone. Third, we argue that while existing and proposed privacy legislation based on the FIPs (Fair Information Practices) will implicitly regulate AI development, they are not sufficient to address societal level privacy harms. Fourth, even legislation that contains explicit provisions on algorithmic decision-making and other forms of AI is limited and does not provide the data governance measures needed to meaningfully regulate the data used in AI systems.

They go on to recommend some solutions:

Denormalize data collection by default by shifting away from opt-out to opt-in data collection. Data collectors must facilitate true data minimization through “privacy by default” strategies and adopt technical standards and infrastructure for meaningful consent mechanisms.

Focus on the AI data supply chain to improve Privacy and data protection. Ensuring dataset transparency and accountability across the entire life cycle must be a focus of any regulatory system that addresses data privacy.

Flip the script on the creation and management of personal data . Policymakers should support the development of new governance mechanisms and technical infrastructure (e.g.,

data intermediaries and data permissioning infrastructure ) to support and automate the exercise of individual data rights and preferences.

In the next section, we’ll focus on how technical solutions (yes, even AI-based ones) could be harnessed to help us maintain Privacy and ownership of our data. I’ll even go one step further and offer some ideas on how AI Companions can be architected to avoid the ability and temptation to leak such data.

Go outside. Touch grass. Take a warm shower.

I promise, there’s a way out of all this.

Title Photo by Lianhao Qu on Unsplash